Although a variety of factors influence the movement of interest rates, the Federal Reserve strongly influences the movement of interest rates through its policies. Through its “Open Market Operations” (the purchase and sale of Treasury securities), the Federal Reserve primarily controls the money supply in the U.S. The amount of money circulating in the economy has an impact on interest rates and credit conditions; more money, lower interest rates. The Federal Reserve targets the fed funds rate, a very short-term interest rate, which is the overnight borrowing rate between banks. The fed funds rate is the central interest rate in the U.S. financial market. When the Federal Reserve changes this rate, there is generally a rippling effect on other interest rates in the financial markets. When the Federal Reserve decreases the fed funds rate (through increasing the money supply by buying Treasury securities in the financial market), other interest rates (interest on liquid assets, mortgage rates, etc.) generally decrease. When the Federal Reserve increases the fed funds rate (by selling from its inventory of Treasury securities and consequently decreasing the money supply), other interest rates generally increase. The goal of the Federal Reserve – balance economic growth with acceptable levels of inflation.

Theoretically the Federal Reserve acts independently to determine what they feel is the best level for interest rates to balance economic growth and inflation. However, the Federal Reserve may face political pressure from the President and/or Congress for a certain interest rate level. The President and/or Congress may have a shorter time frame due to elections. In other words, reduce interest rates now to stimulate economic growth and worry about inflation later.

The Financial Crisis

Although a myriad of factors contributed to the financial crisis, rising interest rates lit the fuse for the economic implosion.

The United States began the new century heading into a recession. The dot.com bubble was over, with overhyped tech and internet stocks crashing to reality. The technology heavy Nasdaq index declined over 75% from a peak of 5,048.62 on March 10, 2000 to 1,139.90 on Oct 4, 2002. The September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks contributing to the economic decline, as uncertainty and fear gripped the economy.

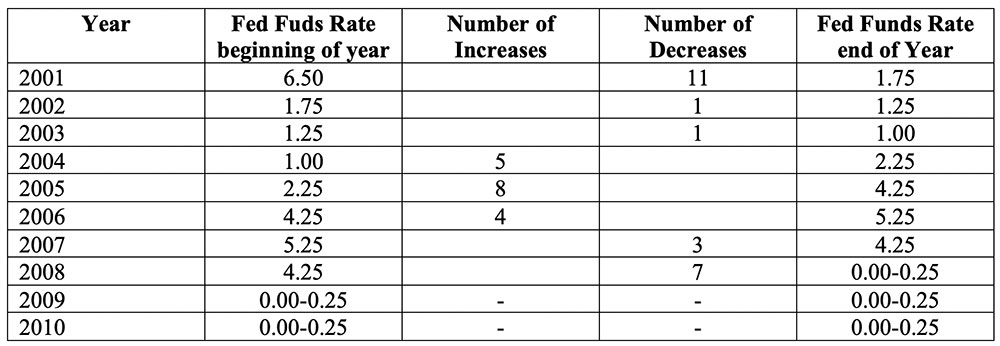

Table 1 below shows the fed funds rate from 2001 through 2010. The Federal Reserve dramatically cut interest rates in 2001 to counter the recession, cutting rates 11 times from 6.50 at the start of the year to a year ending 1.75. Rate cuts occurred again in 2002 and 2003, bringing the fed funds rate to 1.00. As the economy rebounded and concerns over inflation grew, the Federal Reserve increased rates multiple times over the next three years, bringing the rate to 5.25 in 2006. The increasing rate not only dampened the economy, but it also paved the way for increasing monthly mortgage payments on adjustable rate mortgages. The up-tick in interest rates resulted in many home buyers not being able to pay monthly mortgage payments; many homes were put up for sale. The result – home prices plummeted, defaults occurred on mortgage loans and mortgage-backed securities, foreclosures increased significantly, and the economy and stock market began a decline in late 2007 that lasted until early 2009.

The defaults on mortgage loans and mortgage backed securities led to a credit crisis in the financial markets (banks did not have the liquidity to make loans) and a lack of consumer and investment spending by business. The Federal Reserve began slashing interest rates in an effort to counter the negative economic impact of the financial crisis. In 2008 the Federal Reserve cut the fed funds rate 7 times; by year-end, the rate was at a historical low of 0.00-0.25%.

Table 1: Fed Funds Rate 2001–2010

The rock bottom fed funds rate of 0.00-0.25% contributed to an economic recovery that began in July 2009. The Federal Reserve made important contributions to the financial crisis economic recovery, through increasing liquidity in the financial markets, fostering loan availability to consumers and businesses, and decreasing interest rates to historical lows.

When the Federal Reserve changes the fed funds rate, there is generally a rippling effect on other interest rates in the financial markets. This was exemplified by the Treasury yield curve, which shows the relationship between short-term and long-term interest rates on Treasury debt with different maturities. Table 2 below shows the change in short-term and long-term rates between January 1, 2008 and January 1, 2009. Across the board, interest rates on all maturities of Treasury securities declined in 2008 when the fed cut interest rates 7 times.

Table 2: Treasury Yield Curve – January 1, 2008 and January 1, 2009

The COVID-19 Crisis

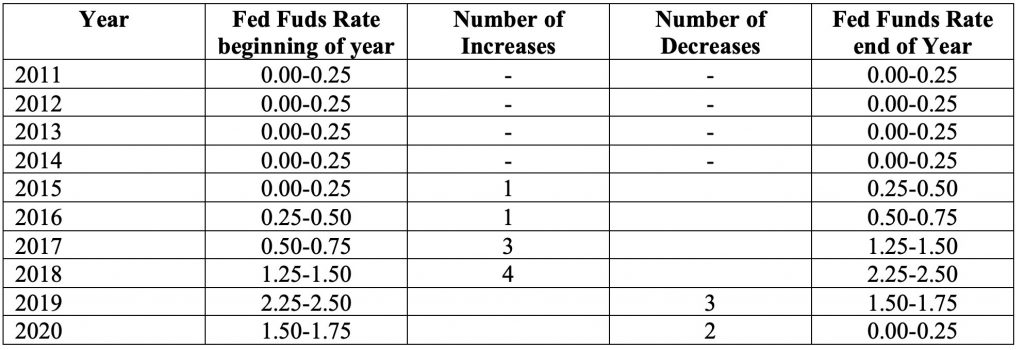

Table 3 below shows the fed funds rate from 2011 through 2020. The 0.00-0.25% fed funds rate that began in 2008 remained in effect through the end of 2015 as economic growth returned and unemployment gradually and consistently declined. Low interest rates contributed to kick-starting and maintaining the longest period of U.S. economic growth that began in July 2009 but abruptly ended in February 2020.

As the economy continued to grow and unemployment approached 50-year lows, the fed funds rate was increased to temper economic growth and limit inflation concerns beginning in 2015. Single rate increases occurred in 2015 and 2016, with multiple rate increases in 2017 and 2018. The 4 rate increases in 2018 were primarily designed to offset the stimulus effects of the 2018 tax law changes. However, that trend reversed in 2019. Concern over a global economic slowdown and the impact of U.S. trade wars and tariffs with China and other countries prompted the Federal Reserve to make multiple rate cuts in 2019. After peaking at 2.25-2.50% in 2018, 3 rate cuts in 2019 lowered the rate to 1.50-1.75% by the year-end.

Table 3: Fed Funds Rate 2011–2020

The negative impact of the coronavirus on the economy prompted two more rate cuts in 2020, and in March 2020 the fed funds rate returned to its historical low of 0.00-0.25%. In each crisis, the financial crisis and the COVID-19 crisis, the fed funds rate was cut to a rock bottom low of 0.00-0.25% to limit the economic damage of the crisis and help the economy rebound. As it did during the financial crisis, the Federal Reserve made important and significant contributions during the COVID-19 crisis through increasing liquidity in the financial markets, fostering loan availability to consumers and businesses, and decreasing interest rates to historical lows.

In the current economic environment, it is quite likely that interest rates will remain low for the foreseeable future. The economic rebound is dependent on controlling the virus and an effective vaccine – both could take some time. Low interest rates will aid a struggling economy. In addition, low interest rates can minimize government debt interest expense. The increasing budget deficits precipitated by the 2018 tax cuts were greatly exacerbated by increased government spending necessitated by the coronavirus. The result – record deficits and skyrocketing government debt. According to the U.S. Treasury, total public debt was $17.2 trillion on January 1, 2020. By August 1, total public debt had increased nearly 20% to $20.6 trillion, providing further incentive for the Federal Reserve to keep interest rates low.

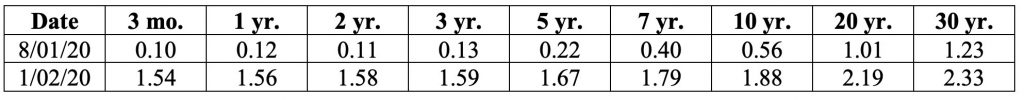

Table 4 below shows the change in short-term and long-term rates between January 2, 2020 and August 3, 2020. The 2019 fed funds rate decreases had already reduced interest rates to extremely low levels by the end of 2019. However, the fed funds rate cuts in 2020 reduced rates to incredibly low levels. Once again across the board, interest rates on all maturities of Treasury securities declined in 2020 as a result of the cuts in the fed funds rate.

Table 4: Treasury Yield Curve – January 1 2020 and August 1, 2020

For further information:

- From the Brookings Institution, details on Fed action during the COVID-19 crisis

- From the Federal Reserve, details on Fed action during the financial crisis

- From the U.S. Treasury, data of U.S. debt outstanding

CBEI Series: A Tale of Two Crises–and Recoveries: Financial Crisis vs. COVID-19 Crisis

Part 1: Causes and Cures

Part 2: Economic Growth – Before and During the Crises

Part 3: Unemployment – Before and During the Crises

Part 4: The Federal Reserve and Interest Rates

Kevin Bahr is a professor emeritus of finance and chief analyst of the Center for Business and Economic Insight in the Sentry School of Business and Economics at the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point.