Another topic that generally gets discussed a lot in economics (and politics) is corporate taxes. It’s also one of the more complex subjects, because it is not always easy to determine what a company actually pays in taxes. It can be done, but it’s not necessarily easy. The primary objective of this blog is to provide some insight on that using General Motors as the example.

One of the most important changes from the 2018 tax bill was the significant reduction in the federal corporate tax rate. The statutory (legal) corporate tax rate was lowered from 35% to 21%. The statutory tax rate is the legal percentage established by law. Does that mean every company will pay a 21% tax rate on its pre-tax income? Well, no. Lowering the statutory rate certainly lowers the taxes paid by a company. However, the effective corporate tax rate, the rate that a company actually pays on pre-tax profits, can be very different from the statutory tax rate. The effective rate can be different from the statutory rate due to tax credits and deductions. And now, an attempt to explain that using General Motors as the example.

General Motors is a public company, meaning that it has sold stock to the general public. Public companies are required by law to disclose their financial statements to the public, which includes information on how the company has been financed, cash flow, revenues, net income, and expenses – including taxes. Because the company sold its stock to the public, the public has a legal right to know about the financial performance of the company. Detailed financial information, including the financial statements, is contained in the company’s “Form 10-K” which is basically a financial report that must be filed annually with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

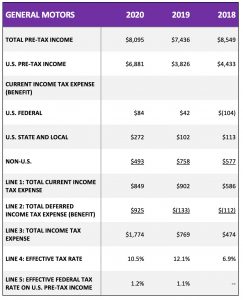

The financial statements include the income statement, which shows the revenue and profit for the firm for a given year. Listed below is selected information taken from the income statements for General Motors for 2020, 2019 and 2018.

General Motors pre-tax income and income tax expense

(in millions of dollars)

Based on the information presented in the income statement, it looks like GM paid over $1.7 billion in taxes in 2020, $769 million in 2019, and $474 million in 2018. Did they? Well, no. The income tax expense indicated on the income statement is NOT what the company paid in taxes in a given year.

Here is where corporate taxes start getting a little complex. Income statements are prepared by companies using certain rules and guidelines (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles) established by the accounting profession. The idea is to match revenues with the expenses incurred to derive those revenues – this determines the “book” income, the amount of income shown on the income statement. However, tax laws can be different from the accounting rules used to prepare the income statement. The “taxable” income on a company’s tax return can be very different from the “book” income reported on the income statement. We’ll return to the GM example and attempt to explain the difference for GM.

The income tax expense reported on GM’s income statement reflects a matching of revenues with expenses per accounting standards. The income tax expense will also reflect the mix of federal, state, local and foreign income taxes when revenues are matched with expenses. However, the income tax expense does NOT reflect what a company actually pays in taxes.

Companies are required to disclose information that indicates how much they paid in income taxes. However, it might take a little ciphering to figure out the exact amount paid. As part of their required financial disclosure, U.S. public companies must disclose a statement of cash flows for a given year and include “notes” to the financial statements. “Notes” are provided as an addendum to the financial statements in the company’s Form 10-K to explain certain items in greater detail, including taxes. The statement of cash flows is meant to provide more detail on how a company’s net income differs from its cash flow. The amount of taxes paid by a corporation can be determined by analyzing the statement of cash flows and the notes to the financial statements.

Select information from the “Note” on income taxes in the General Motors Form 10-K is presented (in millions of dollars) below. Explanations for the numbered lines are presented below the table.

Line 1: The total current income tax expense is the actual tax expense incurred in a given year that must be paid. In 2020, 2019, and 2018, the total current income tax expense for GM was $849 million, $902 million, and $586 million, respectively. These were the total amounts in income taxes that GM was required to pay. Total current income tax expense included U.S. federal income taxes, state and local income taxes, and foreign income taxes. The federal income tax portion was $84 million and $42 million in 2020 and 2019, respectively. In 2018, GM did not pay federal income taxes and received a tax credit (or refund) of $104 million. Note these amounts are significantly lower than the income tax expense shown on the income statement.

Line 2: Deferrals arise because of the difference between the accounting standards used to prepare the financial statements and the tax laws used to prepare the company’s tax return. For example, a very common difference occurs when a company depreciates (allocates) the cost of property, plant, and equipment over time. For the financial statements, the objective is to match revenues with the costs incurred to derive those revenues. Straight-line deprecation (an equal allocation of cost over the life of the property, plant, and equipment) is commonly done in preparing financial statements. However, tax laws may allow accelerated depreciation, which results in a greater allocation of cost (a greater tax deduction) in the early years that the property, plant, and equipment is used. This results in income tax expense on the financial statements exceeding taxes paid.

Rather than depreciating (allocating) the cost of property, plant and equipment over a certain number of years as required previously, the 2018 tax cuts allow companies to fully expense (take a full deduction for) spending on property, plant and equipment (capital spending) through 2022. In other words, an immediate tax benefit for the full amount spent.

Deferred income tax expense implies that the taxes will have to be paid later. In the example used above, in the later years that the property, plant, and equipment is used the amount of straight-line depreciation will exceed any accelerated depreciation. That would result in the current income tax expense (which must be paid) exceeding the income tax expense on the income statement. However, tax laws can change, so deferred income tax expense does not always indicate what will be paid in the future. In addition, the amount listed as a deferral does not take into account the time value of money. If you owed $100 in taxes, would you rather pay it now or in 10 years?

Deferred income tax expense plus the current income tax expense equals the total income tax expense on the income statement.

Line 3: The total income tax expense is the income tax expense reported on GM’s income statement. It takes into account the matching of revenues and expenses per accounting standards and the U.S. federal income tax rate, state and local income tax rate rates, and foreign income tax rates. It is NOT the tax paid in the current year.

Line 4: The effective tax rate is the total current income tax expense divided by the total pre-tax income reported on the income statement. In other words, it is the percentage of total pre-tax income that must be paid in taxes in the current year. In 2020, 2019 and 2018, GM’s effective tax rate on total pre-tax income was 10.5%, 12.1% and 6.9%, respectively.

Line 5: The effective federal tax rate on U.S. pre-tax income is the U.S. federal current income tax expense divided by U.S. pre-tax income. In other words, it is the percentage of U.S. pre-tax income that must be paid in U.S. federal income taxes in the current year. In 2020 and 2019, GM’s effective federal tax rate on U.S. pre-tax income was 1.2% and 1.1%, respectively. The company did not pay federal income taxes in 2018. Note the effective federal tax rate on U.S. pre-tax income is significantly below the statutory rate of 21%. Although companies must disclose income taxes paid, they do not have to disclose why and how their effective federal income tax rate differs from the 21% statutory rate.

Although the statutory U.S. federal income tax rate is 21%, the effective rate may be significantly different for many U.S. companies. A 2019 study by the Institute on Taxation & Economic Policy examined the 2018 effective tax rate for 379 profitable firms included in the Fortune 500. For the 379 companies, the study analyzed the effective U.S. income tax rates on their pretax U.S. profits in 2018. The findings included:

Economic and political discussion on corporate taxes will likely increase in the future. The 2018 tax cuts increased the U.S. budget deficit in a period of economic growth, and the economic impact of COVID-19 caused the budget deficit to increase dramatically. When the economic rebound occurs and growth returns to some degree of normalcy, discussions may ensue on how to effectively balance government spending with government revenues through taxes.

For further information:

- SEC EDGAR Database Company Search Page

- General Motors 2020 Form 10-K

- Corporate Income Tax Brackets and Rates 1909-2002

- Corporate Tax Avoidance in 2018

Kevin Bahr is a professor emeritus of finance and chief analyst of the Center for Business and Economic Insight in the Sentry School of Business and Economics at the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point.