Social Security has been in the news recently, as the topic has again become a subject of political discussion. The conundrum – while workers have paid into the Social Security system for many years expecting to receive a certain level of benefits, the money may not be there when they retire.

Social Security – Who Gets Benefits?

Following the stock market crash in 1929 and the Great Depression, the quest for economic security became elusive for many Americans. President Franklin D. Roosevelt in conjunction with Congress sought to increase the economic security of Americans, particularly in their retirement years. The Social Security Act was an attempt to do that – signed into law by President Roosevelt in 1935, it created a social insurance program designed to pay retired workers age 65 or older a continuing income after retirement.

Social Security was initially focused on retirement benefits, but the program expanded through the years to enhance economic security for a variety of Americans. Key changes included: 1) the addition of a Social Security Disability Insurance program (SSDI) in 1954 under President Eisenhower which provided benefits to disabled workers and disabled adult children, 2) the addition of a medical insurance program for individuals 65 and older (Medicare) in 1964 under President Johnson, 3) the extension of benefits to lower-income and disabled Americans through Social Security Insurance (SSI) in the 1970s under President Nixon, and 4) in response to funding concerns, changes under President Reagan made Social Security payments subject to taxation and raised the retirement age for full benefits in the next century.

In addition to Medicare, Social Security currently pays four types of benefits: 1) Retirement – partial benefits available at age 62; full benefits are a function of birth date, 2) Disability, 3) Survivors – for spouses of workers who have died and are age 60 or older; or who have a dependent child, and 4) Dependents of beneficiaries. Out of those four categories, Retirement is by far the major benefit program, comprising nearly 80% of the benefits paid out.

You don’t automatically receive retirement benefits. You receive one “Credit” for each $1,510 (2022) you earn up to a maximum of four credits per year. Most people need to work 10 years (40 credits) to qualify for retirement benefits; fewer credits are generally needed for disability or survivor benefits. When you start to receive your “full” Social Security retirement benefit is a function of your age and when you were born:

Retirement Age – full benefits (partial benefits available at age 62)

| Year of birth | Full retirement age |

| 1943-1954 | 66 |

| 1955 | 66 and 2 months |

| 1956 | 66 and 4 months |

| 1957 | 66 and 6 months |

| 1958 | 66 and 8 months |

| 1959 | 66 and 10 months |

| 1960 or later | 67 |

The estimated average monthly Social Security benefit for a retired worker in 2022 is $1,657.

Social Security Programs – How They Are Funded

In essence, Social Security programs are funded through payroll taxes. Employees and their employers each pay 6.2% of earnings for Social Security taxes; an additional 1.45% of earnings are paid for Medicare taxes. Medicare is the country’s basic health insurance program for people age 65 and older, and for many people with disabilities. In sum, a total of 15.30% of an employee’s earnings are subject to Social Security and Medicare taxes, with employee and employer each paying 7.65% of an employee’s earnings.

These payroll taxes provide over 90% of the funding for Social Security programs. (Taxes on Social Security benefits and interest on trust fund assets provide the rest.) There is a salary limit for deductions of Social Security taxes. The salary limit is $147,000 in 2022, with the salary limit typically adjusted each year by the approximate level of inflation. Workers who earn more than the taxable maximum do not pay Social Security taxes on that amount or have those earnings factored into their future Social Security payments. There is no wage limit for the Medicare tax. Beginning in 2013, workers pay an additional 0.9 percent Medicare tax on income exceeding certain thresholds: $200,000 for single taxpayers, $250,000 for married.

The Conundrum

If you are thinking that the money you paid into Social Security by you and your employer will be there for you when you retire, well, it’s not. Current payments into Social Security are being dispersed to those receiving benefits now – any excess payments remain in Social Security trust funds. So, money you pay in taxes today is NOT being set aside for your future retirement. If total payments into Social Security exceed program costs in a given year, then the excess money is put into trust funds to fund future program costs. That happened in every year between 1982 and 2020. If program costs exceed payments in a given year, then money is drawn from the trust funds to pay the difference. That happened in 2021, when Social Security’s total cost exceeded its total income for the first time since 1981. Disbursements are expected to continue to exceed program income for the foreseeable future, with money drawn from the trust funds to pay the difference.

Each year the Trustees of Social Security and Medicare release a trust funds report on the current and projected financial status of the programs. According to the 2022 report: “Both Social Security and Medicare face long-term financing shortfalls under currently scheduled benefits and financing.” The report states:

- The Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) Trust Fund, which pays retirement and survivors benefits, is expected to pay scheduled benefits on a timely basis until 2034. At that time, the fund’s reserves will become depleted and continuing tax income will be sufficient to pay only 77 percent of scheduled benefits.

- The Disability Insurance (DI) Trust Fund, which pays disability benefits, is not expected to be depleted within the 75-year projection period.

- The OASI and DI funds are separate entities under law. The report also presents information that combines the reserves of these two funds in order to illustrate the actuarial status of the Social Security program as a whole. The hypothetical combined OASI and DI funds would be able to pay scheduled benefits on a timely basis until 2035. At that time, the combined funds’ reserves will become depleted and continuing tax income will be sufficient to pay only 80 percent of scheduled benefits.

- The Hospital Insurance (HI) Trust Fund, or Medicare Part A, which helps pay for services such as inpatient hospital care, will be able to pay scheduled benefits until 2028. At that time, the fund’s reserves will become depleted and continuing total program income will be sufficient to pay 90 percent of total scheduled benefits.

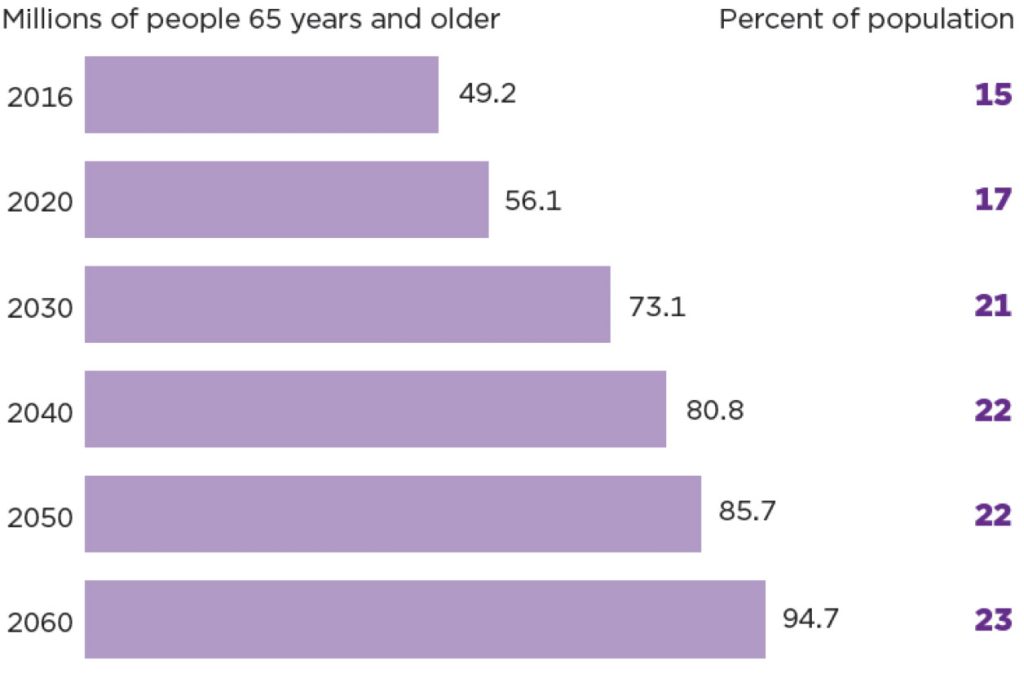

The demographic shifts and aging population in America have created strains in the financing of Social Security programs. The figure below shows the number and percentage of Americans age 65 and older from 2016 through 2060. The number of Americans age 65 and older is expected to almost double over the period, increasing from 15% of the population to 23% of the population.

Figure 1: Americans Aged 65 and Older

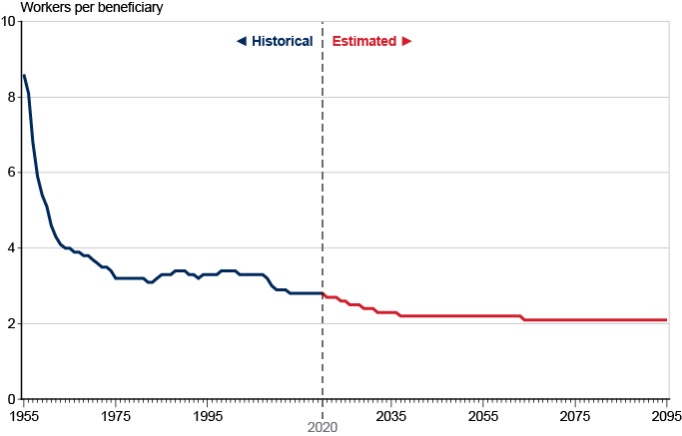

The successful financing of Social Security is predicated on money going in from current workers to money going out to beneficiaries. However, the aging of America and a decreasing worker to beneficiary ratio means that fewer working people are paying for more beneficiaries. The chart below shows the ratio of workers (paying into the system) and beneficiaries (receiving Social Security benefits). That ratio has significantly declined since 1955 and is expected to continue to decline in the future.

Chart 1: Workers per Social Security Beneficiaries

Fewer workers per beneficiary and the aging of America is straining the Social Security system. The current and future funding challenges beg several critical questions. What about the money that workers have put into Social Security after years of employment? How much are they currently scheduled to receive? Rather than paying taxes into Social Security, how much money would workers have if those taxes had been alternatively invested?

Retirement Benefits

The Social Security Administration uses a pretty elaborate formula to determine your retirement benefit. Basically, your benefit at retirement is a function of what you earned over your lifetime. Here’s a brief summary of how a retirement benefit (officially called the “primary insurance amount”) is calculated by Social Security.

- Your historical actual earnings are adjusted or “indexed” to make past earnings reflect what they would be in current dollars. (Only earnings at or below the salary limit for Social Security taxes are considered each year.)

- Social Security calculates your average indexed monthly earnings (AIME) during the 35 years in which you earned the most. The calculation is done by adding all 35 years of indexed earnings together, dividing by 35 to find your annual average, and dividing this result by 12 to determine your lifetime monthly average.

- A fairly complex formula is applied to these earnings to arrive at your basic “full” benefit. This is how much you would receive at your full retirement age — 65 or older, depending on your date of birth as explained earlier. The formula used depends on the year that a person becomes eligible to receive retirement benefits (when they turn 62).

- For 2022, the retirement benefit is calculated as:

- 90% of the first $1,024 of a person’s AIME, plus

- 32% of AIME greater than $1.024 but less than $6,172

- 15% of AIME greater than $6,172

Retirement Benefit Examples

The Social Security Administration website provides two hypothetical, specific examples to demonstrate how retirement benefits are determined. In each case, the worker retires in 2022.

Case A – worker is born in 1960 and retires at age 62. Nominal wages start at $13,587 in 1982 and are assumed to increase to $62,018 in 2021, growing at an approximate annual rate of 3.8%. Because the worker in case A is first eligible for benefits in 2022 and also retires in 2022, there are no applicable cost-of-living-adjustments, or COLAs. The monthly benefit (referred to as the “Primary Insurance Benefit” by Social Security) is $2,079.68. However, because the worker takes Social Security at age 62 before full retirement age (67), the monthly benefit is reduced to $1,455.

Case B – worker is born in 1956 and retires at full retirement age (66 years and 4 months). Earnings in each year are at the wage limit for Social Security taxes. Nominal wages increase from $32,400 in 1982 to $142,800 in 2021. The worker in case B is first eligible in 2018 (the year case B reached age 62). As a result, cost-of-living adjustments will apply. The monthly benefit for 2022 is $3,313.

What if the taxes paid into Social Security (by both the worker and employer) would have been conservatively invested? What would the worker in each case have at retirement?

The table below provides an estimated monthly benefit for the Case A worker and the Case B worker if the Social Security taxes were alternatively invested rather than paid into the Social Security system. The table shows the monthly benefit for the Case A worker and Case B worker given four different scenarios: 1) annual return of 2.0% with life expectancy of 77 years, 2) annual return of 2.0% with life expectancy of 85 years, 3) annual return of 4.0% with life expectancy of 77 years, and 4) annual return of 4.0% with life expectancy of 85 years.

Monthly Retirement Benefit – Invested Funds

| Case A | Case B | Case A | Case B | |

| Annual rate of return | 2.00% | 2.00% | 4.00% | 4.00% |

| Total funds at Retirement | $225,883 | $554,599 | $311,903 | $770,581 |

| Monthly Benefit through Life Expectancy of 77 years | $1,453 | $4,684 | $2,306 | $7,225 |

| Monthly Benefit through Life Expectancy of 85 years | $1,021 | $2,925 | $1,730 | $4,831 |

| Social Security Retirement Benefit | $1,455 | $3,313 | $1,455 | $3,313 |

For the Case A worker, an annual return of 2.0% on the Social Security taxes paid between 1982 and 2021 would provide $225,883 at retirement. That amount would provide a monthly benefit of $1,453 if a monthly benefit was paid through the age of 77 and would provide a monthly benefit of $1,021 if a monthly benefit was paid through the age of 85. This compares to the Social Security retirement benefit of $1,455. An annual return of 4.0% on the Social Security taxes paid between 1982 and 2021 would provide $311,903 at retirement. That amount would provide a monthly benefit of $2,306 if a monthly benefit was paid through the age of 77 and would provide a monthly benefit of $1,730 if a monthly benefit was paid through the age of 85.

For the Case B worker, an annual return of 2.0% on the Social Security taxes paid between 1982 and 2021 would provide $554,599 at retirement. That amount would provide a monthly benefit of $4,684 if a monthly benefit was paid through the age of 77 and would provide a monthly benefit of $2,925 if a monthly benefit was paid through the age of 85. This compares to the Social Security retirement benefit of $3,313. An annual return of 4.0% on the Social Security taxes paid between 1982 and 2021 would provide $770,581 at retirement. That amount would provide a monthly benefit of $7,225 if a monthly benefit was paid through the age of 77 and would provide a monthly benefit of $4,831 if a monthly benefit was paid through the age of 85.

The goal of Social Security when it was created was to increase the economic certainty of Americans in their retirement. It does. For workers that have paid Social Security taxes, the above examples would indicate that although Social Security payments increase economic certainty, those payments are certainly not excessive.

The Future

A variety of changes could be made to the Social Security program to enhance its financial stability. However, at least some political agreement would be required for the changes to occur. That would likely be the hard part. And those changes would have to focus on 1) increasing revenues, 2) decreasing costs, or 3) some combination of increasing revenues and decreasing costs. That’s where the political differences would likely occur. A variety of choices would be available:

- Increasing the retirement age for full benefits in the future

- Increasing payroll taxes

- Lifting the salary limit ($147,000 in 2022) for social security taxes

- Providing another source of funding for Social Security benefits

- Reducing benefits

- Increasing program efficiencies and reducing administrative costs

The examples above indicate that current Social Security payments are not excessive, but the growing demographic imbalance between workers and beneficiaries has caused a financial strain to the system. Certainly, the pending demographic imbalance was obvious for a long time, but changes to Social Security did not occur. In future years, eventually something will have to change regarding funding, program costs, or benefits derived from Social Security. Exactly what gets done will be a political choice.

For further information:

- From the Social Security Administration:

- Social Security Administration (SSA): Social Security History

- Trustee Annual Report Summary

- Old-Age and Survivors Trust Funds

- Disability Insurance Trust Fund

- Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance Trust Funds

- 2022 Social Security Trustees Report

- SS Monthly Statistical Snapshot

- Understanding the Benefits

- Benefit Calculation Example

- Social Security Tax Rate History

Kevin Bahr is a professor emeritus of finance and chief analyst of the Center for Business and Economic Insight in the Sentry School of Business and Economics at the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point.