Funding the federal government (and government shutdowns) has become a hot political topic lately. This blog will explain what the government spends its money on, how the government is financed, and how and why federal debt has increased.

Federal Government Spending

Federal government spending consists of three major categories: mandatory spending, discretionary spending, and spending on net interest. Mandatory spending accounts for approximately two-thirds of total federal government spending, while discretionary spending accounts for approximately 25% and net interest approximately 10% of annual spending.

A key difference between mandatory and discretionary spending is what governs the spending. Mandatory spending is legally required with payments authorized and specified by existing laws; it is not annually approved each year by Congress. Changing mandatory spending would require changing existing laws. Discretionary spending must be appropriated and approved annually by Congress and the president. Spending on net interest is comprised of the government’s interest payments on debt reduced by interest income received by the government. Spending on net interest is largely a function of the total federal debt outstanding.

Mandatory spending includes spending on Social Security, Medicare for the elderly and disabled, and Medicaid for the poor. Mandatory spending is not approved annually by Congress; it is authorized and specified by existing laws. For example, the amount received by Social Security beneficiaries is generally specified by a formula which is based on a person’s earnings history and at what age the beneficiary starts receiving payment. The requirements for receiving Social Security and the benefit received are a function of existing laws. Congress can change the laws governing mandatory spending, but changes in spending would require changes to existing laws.

Discretionary spending includes spending on national defense and non-defense functions, such as infrastructure, transportation, education, housing, social service programs, and science and environmental organizations. Most of spending in the Chips and Science Act of 2022 and the Jobs Act of 2021 (Bipartisan Infrastructure Law), for example, is discretionary spending. Aid to foreign countries, such as Ukraine, is also discretionary spending. Discretionary spending is determined annually by an appropriations process which is approved by both Congress and the president.

A government shutdown occurs if Congress hasn’t approved funding for federal government discretionary spending by the time the new fiscal year starts on October 1. A government shutdown can be temporarily avoided if a short-term funding bill is passed, which is what recently happened on September 30. Supplemental appropriations can be approved if additional funding is needed for discretionary spending. Certain mandatory payments, like Social Security payments to seniors and Americans with disabilities, would continue to be distributed even if the government shuts down.

The Fiscal Responsibility Act, enacted in June 2023, established discretionary spending limits for fiscal years 2024 and 2025 for both defense and nondefense discretionary spending. The limits for defense represent an increase in both fiscal years from fiscal year 2023, while the limits for nondefense represent a decrease in both fiscal years from fiscal year 2023. The Act also suspended the debt ceiling (the total debt that U.S. federal government has outstanding) through January 2025.

The table below breaks down mandatory and discretionary spending in greater detail.

Federal Government Spending by Category, Fiscal Year 2022

The Federal Budget Deficit and Federal Debt

The federal budget deficit refers to the amount U.S. federal government spending exceeds government income, which is primarily derived from tax revenues. To finance a budget deficit, the government borrows money from the public through the issuance of U.S. government debt called U.S. Treasury securities. The Total Public (Federal) Debt Outstanding represents the total (principal) amount of Treasury securities outstanding issued by the federal government. The Debt Limit (also referred to as the debt ceiling) is the maximum amount of money the government is allowed to borrow under authority granted by Congress.

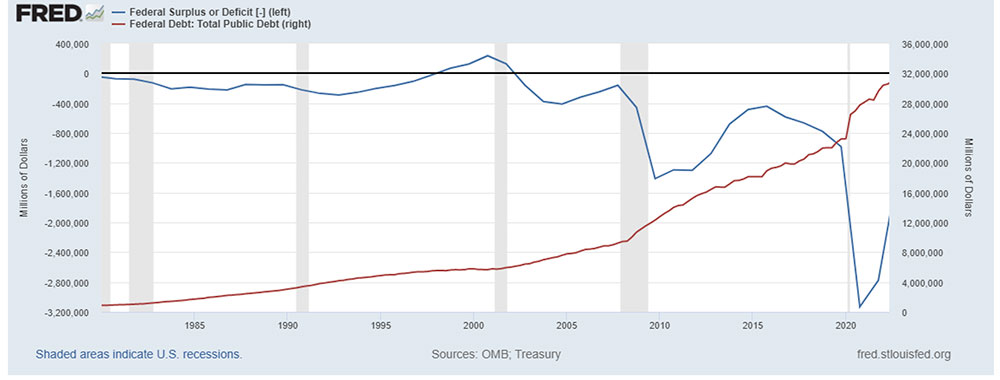

The graph below shows the relationship between federal budget deficits and the total public (federal) debt. The blue line (left axis) indicates the budget deficits or surpluses that have occurred since 1980. Federal government spending has consistently exceeded federal tax revenues since the 1980s. Except for a brief period between 1998 and 2001 when the U.S. was enjoying excellent economic growth and the tech boom in its internet infancy, the United States has had budget deficits since 1980. Major events that played a role in significantly increasing the budget deficit include: 1) the financial crisis of 2008, 2) the tax cuts of 2003 and 2018, and 3) the COVID crisis of 2020.

Economic downturns caused by the financial crisis and COVID had a double whammy on the budget deficit, evidenced by a significant reduction in tax revenues as economic growth turned negative and an increase in fiscal spending to stimulate economic recovery.

The budget deficit usually decreases during periods of economic growth. That, however, changed with the tax cuts of 2018, which contributed to increasing budget deficits during a period of economic growth that began in 2010 and ended with the onset of COVID. Between 2015 and 2019, the budget deficit doubled to over $900 billion. The Congressional Budget Office estimated in 2018 that the tax cut would increase deficits by approximately $1.8 trillion over 11 years. The tax cuts of 2018 occurred during a period of economic expansion and an unemployment rate of only 4.0%. The increasing budget deficit following the tax cuts ensured that a budget surplus was no longer obtainable, based on the tax laws and federal government spending structure in place. The U.S. economy was approaching full employment, yet the budget deficit kept growing. The tax cuts set the stage for a ballooning deficit if something went wrong with the economy, like it did in 2020 with the onset of COVID. In fiscal year 2020, the budget deficit hit a record $3.1 trillion.

The red line (right axis) indicates the total public (federal) debt outstanding. Generally, the public (federal) debt outstanding reflects the accumulation of budget deficits, with subsequent budget deficits increasing the total public (federal) debt outstanding. Between 1980 and 2010, the debt rose from near $0 to approximately $10 trillion. Since 2010, the debt has approximately tripled to over $30 trillion with two major economic downturns and the 2018 tax cuts fueling the increase.

Federal Budget Surplus or Deficit; Total Public Debt

Annual amount of Federal Budget Surplus or Deficit in Millions of Dollars (1980-2022)

Generally, an expanding economy leads to a decrease in the U.S. federal government budget deficit as tax revenues increase. The economic expansion in the 1980s led to the deficit declining slightly in the late 1980s, and the strong economic expansion in the 1990s led to budget surpluses. Following the recession of the early 2000s and the financial and economic crisis of the late 2000s, the deficit once again was reduced when economic growth rebounded. However, the tax cuts of 2018 contributed to a growing budget deficit, and the 2020 stimulus brought the deficit to record levels which in turn pushed total debt to record levels.

Projected Spending, Budget Deficits, and Debt

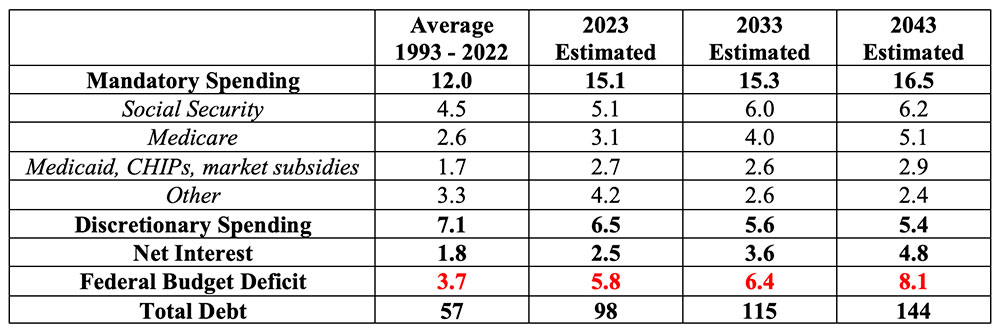

Each year, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) publishes a report presenting its projections of what the federal budget and the economy would look like if current laws generally remained unchanged. The table below includes projections for federal government spending, the budget deficit, and total debt. The projections include the effects of the Fiscal Responsibility Act, which was enacted in 2023. The projections are standardized as a percentage of GDP to show how spending, the budget deficit, and total debt change relative to economic growth.

Long-Term Budget Outlook, June 2023, by Fiscal Year

Percentage of GDP

Key points from the projections:

- The budget deficit and total debt as a percentage of GDP increase significantly. Total debt grows from 98% of GDP in 2023 to 115% in 2033 and 144% in 2044. The budget deficit increases from 5.8% of GDP in 2023 to 6.4% in 2033 and 8.1% in 2044.

- The increases in the budget deficit and total debt are primarily fueled by increases in mandatory spending and net interest; not discretionary spending.

- Mandatory spending increases are driven by Social Security and Medicare. Social Security as a percentage of GDP increases from 5.1% in 2023 to 6.0% in 2033 and 6.2% in 2043. Medicare increases from 3.1% in 2023 to 4.0% in 2033 and 5.1% in 2043.

- Net interest increases with total debt, from 2.5% of GDP in 2023 to 3.6% of GDP in 2033 and 4.8% in 2043.

- Discretionary spending as a percentage of GDP in 2023 is relatively low compared to the historical average and is expected to decrease.

Summarizing the key points, the federal budget deficit and total federal debt outstanding are expected to grow significantly over the next 20 years based on current tax and spending laws. However, the drivers of increased budget deficits and federal debt are mandatory spending and net interest; not discretionary spending. Social Security and Medicare spending are the primary causes of increased mandatory spending.

Social Security and Medicare

Social Security and Medicare spending are expected to fuel expanding budget deficits and growing federal debt over the next 20 years based on current tax and spending laws. The projected increased spending in these programs is a function of the aging of the American population; the shortfall in funding for these programs is a function of how the programs have been financed.

The problems for Social Security and Medicare have been readily foreseeable for decades. The aging of the U.S. population was certainly expected. The graph below shows the percentage of the U.S. population aged 65 and older. In 2001, 12.3% of the population was 65 and older. In 2022, the percentage climbed to 17.1%. The U.S. Census Bureau expects that number to increase to 22% by 2040.

U.S. Population ages 65 and Above

Social Security programs are funded through payroll taxes. Employees and their employers each pay 6.2% of earnings for Social Security taxes; an additional 1.45% of earnings are paid for Medicare taxes. In sum, a total of 15.30% of an employee’s earnings are subject to Social Security and Medicare taxes, with employee and employer each paying 7.65% of an employee’s earnings. The current Social Security and Medicare tax rates have been in effect since 1990. In 1982, Social Security program costs exceeded program income. As a result, key changes were made to Social Security in the 1980s that included extending the full retirement age, increasing payroll taxes, and making Social Security payments subject to taxation. Payroll taxes provide over 90% of the funding (income) for Social Security programs. (Taxes on Social Security benefits and interest on trust fund assets provide the rest.)

There is a salary limit for Social Security taxes. The salary limit is $160,200 in 2023, with the salary limit typically adjusted each year by the approximate level of inflation. Workers who earn more than the taxable maximum do not pay Social Security taxes on that amount or have those earnings factored into their future Social Security payments. There is no wage limit for the Medicare tax. Beginning in 2013, workers pay an additional 0.9 percent Medicare tax on income exceeding certain thresholds: $200,000 for single taxpayers, $250,000 for married.

If you are thinking that the money you paid into Social Security by you and your employer will be there for you when you retire, alas, it’s not. Current payments into Social Security are being dispersed to those receiving benefits now – any excess payments remain in Social Security trust funds. So, money you pay in taxes today is NOT being set aside for your future retirement. If total payments into Social Security exceed program costs in a given year, then the excess money is put into trust funds to fund future program costs. That happened in every year between 1983 and 2020. If program costs exceed payments into Social Security (largely payroll taxes), then money is drawn from the trust funds to pay the difference. That happened in 2021, when Social Security’s total cost exceeded its total income for the first time since 1982. Disbursements are expected to continue to exceed program income for the foreseeable future, with money drawn from the trust funds to pay the difference. Current payments into Social Security being dispersed to current beneficiaries set the stage for financial difficulties if the demographics of the U.S. shifted to an aging population.

The aging of the U.S. population created financing problems for Social Security – fewer young people are paying into the system and more older people are receiving payments from the system. And the money previously paid by older workers into the system was paid to current beneficiaries, not escrowed into an account for their behalf. In 2000 there were approximately 3.5 workers paying into Social Security for every beneficiary; in 2023 there are approximately 2.7 workers for every beneficiary. That is expected to drop to 2.3 workers in 2035.

Each year the Trustees of Social Security and Medicare release a trust funds report on the current and projected financial status of the programs and trust funds. According to the 2023 report: “As in prior years, we found that the Social Security and Medicare programs both continue to face significant financing issues.” Key points from the report:

- The Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) Trust Fund, which pays retirement and survivors benefits, is expected to pay scheduled benefits on a timely basis until 2033. At that time, the fund’s reserves will become depleted and continuing tax income will be sufficient to pay only 77 percent of scheduled benefits.

- The Hospital Insurance (HI) Trust Fund, or Medicare Part A, which helps pay for services such as inpatient hospital care, will be able to pay scheduled benefits until 2031. At that time, the fund’s reserves will become depleted and continuing total program income will be sufficient to pay 90 percent of total scheduled benefits.

In 2023, the Social Security Administration estimates the average monthly benefit for all retired workers at $1,827, or $21,924 annually. By 2033, fund reserves will only be sufficient to pay only 77% of scheduled retirement benefits. If that reduction applied to the current year, the average monthly benefit would be only $1,407, or $16,884 annually. That would be slightly above the 2023 federal poverty income level of $14,580 for one person.

The importance of Social Security is reflected by the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances, which indicated that approximately one-third of American families have no retirement plan other than Social Security. Vanguard, one of the largest investment firms in America, provides information on client retirement account balances by age on an annual basis. According to Vanguard, the median defined contribution (401k) account balance for clients aged 65 and above was $70,620 as of 2022.

Social Security faces significant financing issues, which were readily foreseeable for decades. However, cutting Social Security benefits would cause financial duress for many families, and penalize workers that have paid payroll taxes for decades.

For further information:

- From the U.S. Treasury, actual spending: Fiscal Spending Overview and Spending Categories

- From USAspending, fiscal year obligated spending: Government Spending Explorer | USAspending

- From the Congressional Budget Office:

- From Brookings, info on Discretionary Spending: What is Discretionary Spending in the Federal Budget?

- From McKinsey, info on Inflation Reduction Act spending: Inflation Reduction Act

- From the U.S. Census Bureau: Demographic Turning Points in the U.S.

- From Social Security, annual trust fund income and costs: Trust Fund Data (ssa.gov)

- A summary of the financial status of Social Security from the Trustees: https://www.ssa.gov/OACT/TRSUM/index.html

- Social Security Fact Sheet and Benefit Example

- From the Federal Reserve: Survey of Consumer Finances

- From Vanguard: How America Saves 2023

- From the Congressional Research Service: Fiscal Responsibility Act Discretionary Spending Caps

Kevin Bahr is a professor emeritus of finance and chief analyst of the Center for Business and Economic Insight in the Sentry School of Business and Economics at the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point.