The Federal Reserve has been in the spotlight recently as the great debate over interest rates, specifically the lowering of interest rates, has been the subject of much discussion both economically and politically. The economy is significantly impacted by monetary and fiscal policies of the U.S. government. Fiscal policy includes government spending and tax policies, which historically have been implemented through a combination of presidential and congressional actions. The Federal Reserve is responsible for monetary policy, which is implemented primarily through targeting the fed funds rate by controlling the money supply. This blog will provide a brief overview of the Federal Reserve, followed by a detailed look at Federal Reserve policy this century and when, and why, interest rate changes occurred.

The Federal Reserve

The Federal Reserve System is the central bank of the United States and was created by an act of Congress that was signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson on December 23, 1913. The Federal Reserve System consists of a Board of Governors and 12 regional Federal Reserve banks located in major cities throughout the nation. The Board of Governors is a central, independent governmental agency, and led by the Chairman of the Federal Reserve. The chairman serves a four-year term after being nominated by the President and confirmed by the Senate. A chairman may serve multiple terms, each requiring a nomination by the President and confirmation by the Senate. The current chair, Jerome Powell, began serving his first term in 2018 after being nominated by President Trump and confirmed by the Senate. He received a subsequent term after being nominated by President Biden and confirmed by the Senate in 2022. The Chairman and the Board of Governors strive to serve as a nonpartisan, independent body when implementing monetary policy for the United States.

The Federal Reserve is responsible for monetary policy – implemented primarily through targeting the federal (fed) funds rate by controlling the money supply. The fed funds rate is the overnight borrowing rate between banks, a very short-term interest rate that when changed, typically has a rippling effect through the financial markets. The Federal Reserve influences this rate by primarily controlling the money supply in the United States. The amount of money circulating in the economy has an impact on interest rates and credit conditions – more money, lower interest rates; less money, higher interest rates. The fed funds rate is increased when the Federal Reserve decreases the money supply by selling Treasury securities (technically called Open Market Operations). The fed funds rate is decreased when the Federal Reserve increases the money supply by buying Treasury securities. Changes in the fed funds rate generally affect savings and borrowing rates.

There are actually three tools that the Federal Reserve controls to fully implement monetary policy: 1) open market operations, the buying and selling of financial securities, to change interest rates (the fed funds rate), 2) the discount rate, which is the rate at which financial institutions can borrow from the Federal Reserve, and 3) reserve requirements, which determine the amount of cash that financial institutions must hold to cover possible withdrawals. The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System is responsible for the discount rate and reserve requirements. A separate committee, the Federal Open Market Committee, is responsible for open market operations and meets periodically to discuss changes in interest rates.

In sum, the Federal Reserve is responsible for monetary policy, oversees the financial stability of the banking system, supervises and regulates banking institutions, and provides financial services to depository institutions, the U.S. government, and foreign official institutions.

The Federal Reserve Dual Mandate

Since its founding in 1913, the role of the Federal Reserve has been modified. The Federal Reserve Reform Act of 1977 requires the Fed to direct its policies toward the dual mandate of achieving maximum employment and price stability and report regularly to Congress. To achieve these goals, the Federal Reserve acts in a nonpartisan, independent manner to balance economic growth (which affects employment) with inflation. The goals are met through the application of monetary policy, generally through changes in interest rates. Lower interest rates can increase consumer and business spending which fuels economic growth and boosts employment. However, too much economic growth, or economic growth when the economy is near full employment, can increase inflation. Higher interest rates can lower economic growth by reducing interest rate sensitive consumer and business spending, which generally lowers the demand for products and services and consequently inflation.

Pushing interest rates too high, however, could plunge the economy into a recession. It’s a balancing act for the Federal Reserve, setting interest rates neither too low nor too high, but at a level that promotes economic growth (and full employment) and price stability in the long-run. Setting the appropriate level for interest rates is particularly challenging when the Federal Reserve is trying to lower inflation when there are factors contributing to inflation that are largely outside of the Federal Reserve’s control.

In sum, the Federal Reserve, since 1977, has had a dual mandate of achieving maximum employment and price stability. The Federal Reserve has a specific definition for price stability:

- “The Federal Open Market Committee judges that an inflation rate of 2% over the longer run, as measured by the annual change in the price index for personal consumption expenditures, is most consistent with the Fed’s price mandate.”

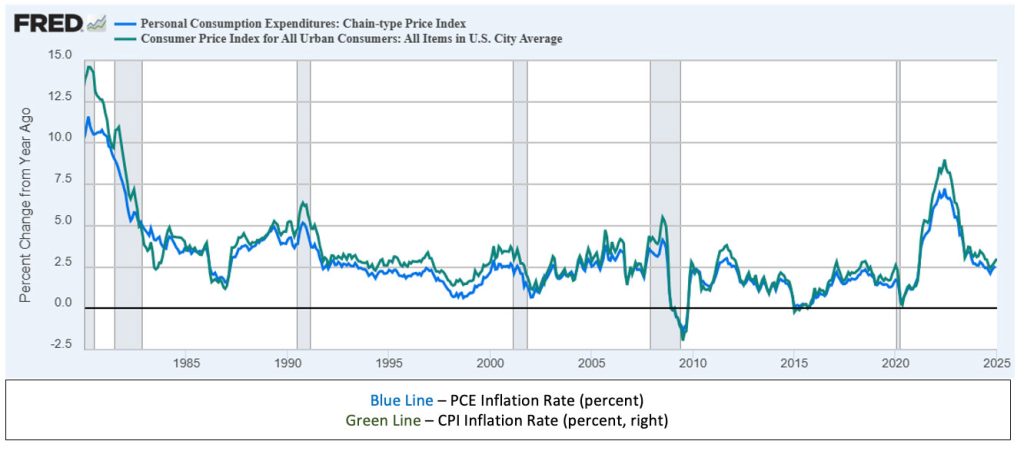

When making monetary policy and interest rate decisions, the Federal Reserve focuses on price changes using the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) index rather than the Consumer Price Index (CPI). Both indexes calculate the price level by pricing a basket of goods. The basket of goods for the two measures is slightly different, and the index weighting of goods is also slightly different. While the two are similar, the PCE index reflects how Americans are currently spending their money to a greater degree and more quickly adapts to changes in spending patterns. The change in the PCE price index captures inflation (or deflation) across a wide range of consumer expenses and reflects changes in consumer behavior. The Federal Reserve seeks to achieve inflation at a 2% rate over the long-run as measured by the annual change in the PCE price index.

Historically, movements in the CPI and PCE index have been very similar, although inflation as measured by the CPI is generally slightly higher. The graph below shows the annual inflation rate, as measured by changes in prices from one year ago, for the CPI (green line) and PCE index (blue line), since 1980.

CPI and PCE Index, Percent Change from One Year Ago

The Federal Reserve has a dual mandate of achieving maximum employment and price stability, and will monitor inflation as employment increases in making policy decisions. While the Federal Reserve has defined price stability, defining exactly what maximum employment is in terms of an absolute number is not easy. The Federal Reserve puts it this way:

- “Maximum employment is the highest level of employment or lowest level of unemployment that the economy can sustain while maintaining a stable inflation rate. Given the dynamic nature of the economy, it is not possible to know exactly how low the unemployment rate may be able to fall in a sustained way without causing excessive inflation. As it seeks to judge how far the economy is from maximum employment, the Fed will assess a wide range of information on the labor market and not rely too much on any single estimate of a sustainable longer-run unemployment rate. Furthermore, the Federal Open Market Committee aims to pursue its maximum employment objective so that very low unemployment without any evidence of higher inflation or other risks is not itself a cause for policy concern.”

Maximum employment is an objective, but the Federal Reserve will monitor inflation as employment increases to make policy decisions. In assessing the labor market, the Federal Reserve will consider not only the unemployment rate, but also total employment, changes in real wages, the labor force participation rate, and the number of job openings relative to the number of people looking for work.

It became clear in the latter stages of the economic recovery in the last decade that an unemployment rate hovering around 3.5% could be sustained without leading to excessive inflation. In reality, it has been very difficult in recent history to move the unemployment rate below 3.5%, as there will always be a mismatch to some degree between the abilities of people looking for work and the skills required for available jobs. Since 1970, only one month had an unemployment rate below 3.5% – April 2023, at 3.4%.

The Fed Funds Rate, Inflation and Unemployment

The Federal Reserve has generally lowered the fed funds rate to stimulate economic growth and increase employment in periods of economic recession or low economic growth. The Federal Reserve has generally increased the fed funds rate to lower interest rate sensitive consumer and business spending, particularly when employment is strong, during periods of relatively high inflation. The Federal Reserve, however, cannot address factors contributing to inflation outside its control, such as supply chain problems, energy and commodity price spikes caused by war, housing inventory shortages, and food price increases caused by bird flu.

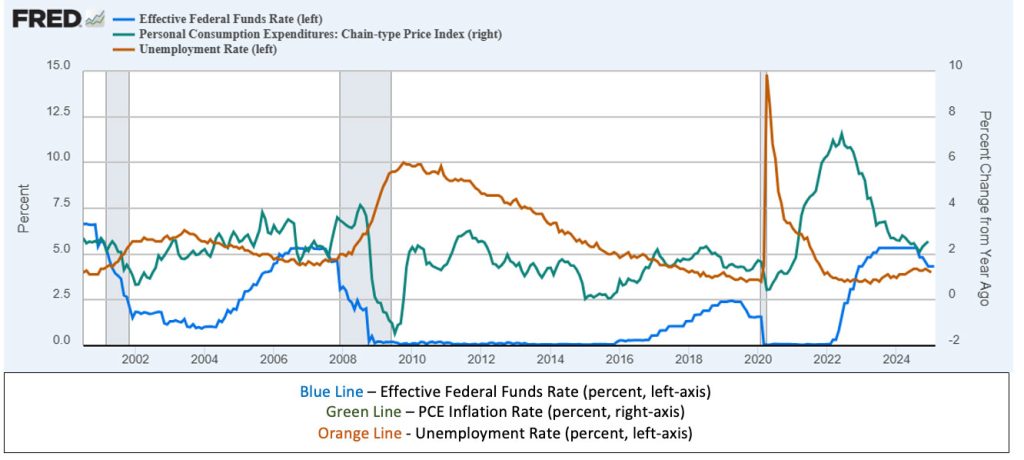

The graph below shows the relationship since 2000 between the effective federal funds rate, unemployment rate, and the PCE inflation rate (as measured by the change in prices for personal consumption expenditures from one year ago). The effective federal funds rate is the market rate targeted by the Federal Reserve through open market operations. The effective federal funds rate is shown by the blue line (left-axis), the unemployment rate is given by the orange line (left-axis), and the PCE inflation rate is shown by the green line (right-axis). Recession periods are shaded.

Effective Federal Funds Rate, PCE Inflation Rate, Unemployment Rate

July 2000 – December 2024

The century began with the fed funds rate target at 5.50%, the unemployment rate at 4.0%, and PCE inflation approaching 3.0%. The fed funds rate target had been increased beginning in 1999 to counter growing inflation resulting from excellent economic growth during the 1990s. The targeted fed funds rate was 4.75% in January 1999 and increased to 6.50% in May 2000. Between 1998 and early 2000, PCE inflation had grown from less than 1% to nearly 3.0%. In 2001, a brief recession occurred due to a variety of bumps to the economy. The dot.com bubble was over, with overhyped tech and internet stocks crashing back to reality. The technology heavy Nasdaq index declined over 75% between March 2000 and October 2002. The September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks contributed to the economic decline, as uncertainty and fear gripped the economy. In addition, the financial markets were plagued by accounting scandals (Enron). Although GDP growth was positive for the entire 2001 year at 1.0%, economic growth was negative for two quarters resulting in a minor recession. The unemployment rate jumped from 3.9% in December 2000 to 5.7% by the end of 2001. PCE inflation fell from 2.7% in January 2001 to just over 1.0% by the end of the year.

The economic recession and jump in unemployment caused a reversal in Federal Reserve policy in 2001. The fed funds rate was lowered from 6.5% at the start of 2001 to 1.00% in 2003. Monetary policy, through interest rate cuts, and fiscal policy, brought the economy out of recession. Although economic growth returned the unemployment rate remained stubbornly high and hovered around 6% through October 2003 before gradually declining. As economic growth increased following the 2001 recession, unfortunately, so did prices. After bottoming out at 0.7% in February 2002, PCE inflation consistently and gradually increased to 3.8% by September 2005. The ramp up in inflation caused another reversal in Federal Reserve policy, and the fed funds rate began increasing in 2004. From a low of 1.00% in 2003, the Federal Reserve raised the fed funds rate 17 times between 2004 and 2006, with the rate peaking at 5.25% in late 2006. Despite the rate increase, the unemployment rate declined to 4.4% by the end of 2006 after peaking at 6.0% in October 2003. PCE inflation peaked at 3.8% in September 2005 before dropping to 1.7% in October 2006. The Federal Reserve policy of increasing interest rates reduced inflation while the labor market remained relatively strong. Rising interest rates, however, played a role in the next major economic crisis.

By late 2007, a major shock to the U.S. economy was beginning in the housing market. Credit was easy and mortgage-backed securities allowed a transfer of risk from lenders to investors. Although a myriad of factors contributed to the financial crisis, rising interest rates and lack of government oversight of the housing market lit the fuse for the economic implosion. Increasing rates not only dampened the economy, but they also paved the way for increasing monthly mortgage payments on adjustable-rate mortgages. The result was that many home buyers were not able to pay mortgage payments and homes were put up for sale. Home prices plummeted, defaults occurred on mortgage loans and mortgage-backed securities, foreclosures increased significantly, and the economy and stock market began a decline in late 2007 that lasted until early 2009 (the S&P 500 declined by nearly 60%). The unemployment rate soared from 4.4% in May 2007 to a peak of 10.0% in October 2009 with the economic recession. Although PCE inflation hit 4.1% in July 2008, one year later prices actually declined, with PCE inflation of -1.5% in July 2009.

The Federal Reserve slashed the fed funds rate three times in late 2007 and seven times in 2008 to spur consumer and business spending as the economy struggled from the financial crisis recession. In December 2008, the fed funds rate was targeted at a record low of 0.00-0.25%. The rate cuts, combined with fiscal policy, led to the longest economic expansion in U.S. history, between June 2009 and February 2020. Throughout the economic expansion, the PCE inflation rate was generally low and relatively stable. PCE inflation peaked in September 2011 at 3.0% as prices and the economy recovered from the financial crisis, but generally hovered around 1.5% throughout the economic expansion. The unemployment rate began a long, gradual decline after peaking at 10.0% in October 2009. The improving labor market and low inflation kept the targeted fed funds rate unchanged at 0.00-0.25% until 2015. Between 2015 and 2018 the fed funds rate was increased slightly as inflation, although low, was increasing. The unemployment rate, however, continued declining. After starting 2019 at 2.25-2.50%, three interest rate cuts occurred as economic growth slowed, and the targeted fed funds rate ended the year at 1.50-1.75%. The unemployment rate bottomed out and hovered around 3.5% in late 2019.

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic as an economic shock led to record unemployment of 14.8% in April 2020 and the loss of over 20 million jobs. The impact of COVID on the economy precipitated another two rate cuts in early 2020 and the fed funds rate returned to its record low of 0.00-0.25% in March.

Monetary policy, including interest rate cuts, and fiscal policy, contributed to a return of economic growth in the second half of 2020 that continued through 2024. The unemployment rate bottomed out at 3.4% in April 2023, the lowest level since 1969. Since then, the unemployment rate has hovered around 4%.

A variety of factors, outside of the Federal Reserve’s control, contributed to a spike in global inflation as the economy recovered. Housing prices started to increase sharply in 2020 as inventory dropped significantly. Global inflation increased in 2021 as supply chain problems appeared and global oil prices began rising due to the economic recovery. In 2022, price spikes in global energy and food prices due to Putin’s invasion of Ukraine and lingering supply chain issues contributed significantly to inflation. The economic recovery, aided by fiscal policy, contributed to a strong labor market with rising real wages. PCE inflation peaked at over 7.2% in June 2022.

In 2022 the focus of the Federal Reserve, and central banks around the world, shifted to increasing interest rates to fight inflation. The objective of the rate increases was to lower consumer and business spending, which in turn would lower inflation by reducing demand for goods and services even though global factors were the primary drivers of inflation. From a historic low of 0.00-0.25%, the fed funds rate hit 5.25-5.50% in July 2023.

PCE inflation gradually declined from a peak of 7.2% in June 2022 to 2.1% by September 2024. The demise of global inflation led central banks around the world to cut interest rates in 2024. In September, the Federal Reserve finally provided a long-awaited interest rate cut, as the fed funds rate was decreased 50 basis points to a target range of 4.75%-5.00%. The decline in inflation, and cooling of the U.S. labor market, contributed to the Federal Reserve’s decision to cut interest rates. Two more 25-basis point cuts occurred in November and December, and the fed funds rate ended 2024 at 4.25%-4.50%. The rate cuts followed eleven rate increases that occurred across 2022 and 2023.

Summary and 2025 Interest Rate Expectations

This century, the Federal Reserve lowered the fed funds rate to stimulate economic growth and increase employment in periods of economic recession or low economic growth. Interest rate cuts occurred in 2000-2003, 2007-2008, and 2019-2020. The Federal Reserve has generally increased the fed funds rate to lower interest rate sensitive consumer and business spending when inflation was relatively high or increasing. Interest rate increases occurred in 2004-2007, 2015-2018 and 2022-2023.

As 2025 began, the controversy, both politically and economically, was how quickly, if at all, further interest rate cuts would occur. Multiple cuts to the fed funds target rate occurred in 2024 as inflation had dropped significantly and the labor market cooled, although unemployment remained relatively low. The 2024 rate cuts were not necessary to pull the economy out of recession or due to weak economic growth. Moderate economic growth continued in 2024; the objective of the rate cuts was to sustain it. The unemployment rate increased slightly in 2024, but remained at a relatively low 4.2% in December and job gains occurred in every month. Inflation had decreased significantly and consistently from the highs of 2022, with PCE inflation falling from its peak of 7.2% in June 2022 to 2.1% in September 2024.

In its September 2024 economic projections for 2025, the Federal Reserve expected the fed funds rate to be targeted at 3.4% by the end of 2025, a decline from the target of 4.25%-4.50% at the beginning of the year. However, PCE inflation increased slightly to close 2024 and ended the year at 2.6%. As a result of inflation increasing and remaining above the 2% target level, in December 2024 the Federal Reserve revised and raised its projection for the fed funds rate at the end of 2025, from 3.4% to 3.9%. In other words, although rate cuts were expected in 2025, the expectation for the number and magnitude of rate cuts declined.

The United States entered 2025 with the largest and strongest economy in the world. Since January, however, inflation persisted, consumer spending declined, and growing economic uncertainty contributed to a decline in consumer confidence. The on-again off-again U.S. tariffs played the stock market like a yo-yo. On-again tariffs contributed to significant stock market declines. Fears of stagflation, weak (if any) economic growth with inflation, spread through financial markets.

The Federal Reserve faces a quandary. Lowering interest rates can spur economic growth, but greater consumer demand can increase inflation in a period where higher tariffs already put pressure on prices. Increasing interest rates to lower inflation could lower interest rate sensitive consumer and business spending, but higher interest rates in a period of declining economic growth could lead to an even greater economic contraction.

At its March 2025 meeting, the Federal Reserve decided to keep the fed funds rate unchanged at 4.25%-4.50%. The Federal Reserve continued its projection for two interest rate cuts in 2025 and a yearend fed funds rate of 3.9%. Relative to its December 2024 economic forecast for 2025, expectations for economic growth declined while inflation increased. The Federal Reserve stressed that its economic projections were subject to a very high level of uncertainty, particularly stemming from the unknown effects of tariff policies. Barring any emergency meetings, the next Federal Reserve meeting to discuss interest rate changes will be May 6-7.

The Federal Reserve makes interest rate policy projections based on economic expectations. The economic expectations for 2025 are certainly subject to revision, and the impact of any newly imposed tariffs on the economy and prices raises the uncertainty. The Federal Reserve strives to act in a nonpartisan, independent manner to implement policies for the long-term benefit of the U.S. economy. Ultimately, providing the Federal Reserve maintains its independence, policy and interest rate decisions will be guided by their dual policy mandate of achieving maximum employment and price stability.

For Further Information:

- From the Federal Reserve:

- Info from the Bureau of Labor Statistics:

- From the Bureau of Economic Analysis:

- From the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland: PCE and CPI Inflation – What’s the Difference?

- From the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond: Origins of the 2% Inflation Target

- From the Federal Reserve of Atlanta: Federal Reserve of Atlanta GDP Projection

- From the Conference Board: Consumer Confidence

- CME FedWatch Tool: CME Fed Funds Futures

Kevin Bahr is a professor emeritus of finance and chief analyst of the Center for Business and Economic Insight in the Sentry School of Business and Economics at the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point.