The Federal Reserve and its chairman, Jerome Powell, have been in the spotlight recently for a variety of reasons, including the lowering of interest rates, Federal Reserve independence, and legal issues. The economy is significantly impacted by monetary and fiscal policies of the U.S. government. Fiscal policy includes government spending and tax policies, which historically have been implemented through a combination of Presidential and Congressional actions. The Federal Reserve is responsible for monetary policy, which is implemented primarily through targeting the fed funds rate by controlling the money supply. The financial markets have generally viewed the ability of the Federal Reserve to operate independently, without interference from Congress or the President, as critically important to the long-term growth of the United States economy and financial market performance.

Federal Reserve Structure

The Federal Reserve System is the central bank of the United States and was created by an act of Congress that was signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson on December 23, 1913. The Federal Reserve System consists of a Board of Governors and 12 regional Federal Reserve banks located in major cities throughout the nation. The Board of Governors is a central, independent governmental agency, and led by the Chairman of the Federal Reserve. The Board consists of seven members appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate, serving staggered 14-year terms. By law, the President can only remove Fed governors for “cause.” Exactly what constitutes cause was not defined, but it may be determined by the Supreme Court. Prior to the current administration, no Fed governor was ever fired by a President.

The Chairman of the Federal Reserve serves a four-year term after being nominated by the President and confirmed by the Senate. A chairman may serve multiple terms, each requiring a nomination by the President and confirmation by the Senate. The current chair, Jerome Powell, began serving his first term in 2018 after being nominated by President Trump and confirmed by the Senate. He received a subsequent term after being nominated by President Biden and confirmed by the Senate in 2022. Powell’s term as chair is scheduled to end in May 2026. The Chairman and the Board of Governors strive to serve as a nonpartisan, independent body when implementing monetary policy for the United States.

The Federal Reserve conducts monetary policy, including the setting of interest rate levels, through the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). The FOMC consists of 12 members–the seven members of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System; the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York; and four of the remaining eleven Federal Reserve Bank presidents, who serve one-year terms on a rotating basis. The FOMC holds eight regularly scheduled meetings per year and determines the appropriate level of interest rates based on a review of economic and financial conditions. Meetings of the FOMC include the seven members of the Board of Governors and all 12 Federal Reserve Bank presidents. The diversified geographical background of the nineteen leaders provides a broad discussion of economic and financial conditions across the country in determining monetary policy and interest rate levels. However, only the 12 members comprising the FOMC will vote on the appropriate level for interest rates and any changes. Interest rates are not unilaterally set by the chairman of the Federal Reserve; the FOMC votes on the implementation of any interest rate change. The chair guides the FOMC to try and reach a consensus regarding interest rate policy, but the chair’s vote only has the same weight as other FOMC members.

Monetary Policy

The Federal Reserve is responsible for monetary policy – implemented primarily through targeting the federal (fed) funds rate by controlling the money supply. The fed funds rate is the overnight borrowing rate between banks, a very short-term interest rate that when changed, typically has a rippling effect through the financial markets. The amount of money circulating in the economy has an impact on interest rates and credit conditions – more money, lower interest rates; less money, higher interest rates. The fed funds rate is increased when the Federal Reserve decreases the money supply by selling Treasury securities (technically called Open Market Operations). The fed funds rate is decreased when the Federal Reserve increases the money supply by buying Treasury securities. Changes in the fed funds rate generally affect savings and borrowing rates.

There are actually three tools that the Federal Reserve controls to fully implement monetary policy: 1) open market operations, the buying and selling of financial securities, to change interest rates (the fed funds rate), 2) the discount rate, which is the rate at which financial institutions can borrow from the Federal Reserve, and 3) reserve requirements, which determine the amount of cash that financial institutions must hold to cover possible withdrawals. The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System is responsible for the discount rate and reserve requirements. A separate committee, the Federal Open Market Committee, is responsible for open market operations and changes in interest rates.

In sum, the Federal Reserve is responsible for monetary policy, oversees the financial stability of the banking system, supervises and regulates banking institutions, and provides financial services to depository institutions, the U.S. government, and foreign official institutions.

The Federal Reserve Dual Mandate

Since its founding in 1913, the role of the Federal Reserve has been modified. The Federal Reserve Reform Act of 1977 requires the Fed to direct its policies toward the dual mandate of achieving maximum employment and price stability and report regularly to Congress. To achieve these goals, the Federal Reserve acts in a nonpartisan, independent manner to balance economic growth (which affects employment) with inflation. The goals are met through the application of monetary policy, generally through changes in interest rates. Lower interest rates can increase consumer and business spending which fuels economic growth and boosts employment. However, too much economic growth, or economic growth when the economy is near full employment, can increase inflation. Higher interest rates can lower economic growth by reducing interest rate sensitive consumer and business spending, which generally lowers the demand for products and services and consequently inflation.

Pushing interest rates too high, however, could plunge the economy into a recession. It’s a balancing act for the Federal Reserve, setting interest rates neither too low nor too high, but at a level that promotes economic growth (and full employment) and price stability in the long-run. Setting the appropriate level for interest rates is particularly challenging when the Federal Reserve is trying to lower inflation when there are factors contributing to inflation that are largely outside of the Federal Reserve’s control.

In sum, the Federal Reserve, since 1977, has had a dual mandate of achieving maximum employment and price stability. The Federal Reserve has a specific definition for price stability:

- “The Federal Open Market Committee judges that an inflation rate of 2% over the longer run, as measured by the annual change in the price index for personal consumption expenditures, is most consistent with the Fed’s price mandate.”

The Federal Reserve has a dual mandate of achieving maximum employment and price stability, and will monitor inflation as employment increases in making policy decisions. While the Federal Reserve has defined price stability, defining exactly what maximum employment is in terms of an absolute number is not easy. The Federal Reserve puts it this way:

- “Maximum employment is the highest level of employment or lowest level of unemployment that the economy can sustain while maintaining a stable inflation rate. Given the dynamic nature of the economy, it is not possible to know exactly how low the unemployment rate may be able to fall in a sustained way without causing excessive inflation. As it seeks to judge how far the economy is from maximum employment, the Fed will assess a wide range of information on the labor market and not rely too much on any single estimate of a sustainable longer-run unemployment rate. Furthermore, the Federal Open Market Committee aims to pursue its maximum employment objective so that very low unemployment without any evidence of higher inflation or other risks is not itself a cause for policy concern.”

Maximum employment is an objective, but the Federal Reserve will monitor inflation as employment increases to make policy decisions. In assessing the labor market, the Federal Reserve will consider not only the unemployment rate, but also total employment, changes in real wages, the labor force participation rate, and the number of job openings relative to the number of people looking for work.

It became clear in the latter stages of the economic recovery in the last decade that an unemployment rate hovering around 3.5% could be sustained without leading to excessive inflation. In reality, it has been very difficult in recent history to move the unemployment rate below 3.5%, as there will always be a mismatch to some degree between the abilities of people looking for work and the skills required for available jobs. Since 1970, only one month had an unemployment rate below 3.5% – April 2023, at 3.4%.

The Importance of Federal Reserve Independence

The Federal Reserve currently operates with independence regarding monetary policy, but not without accountability. The Federal Reserve is required to report to Congress twice a year and discuss monetary policy decisions, with the Fed Chair testifying before Congress. In 1977, Congress charged the Federal Reserve with the objectives of maximum employment and stable prices when implementing monetary policies. Congress could alter the law, but the broad expertise of Federal Reserve members, the democratic process of the Federal Open Market Committee, and nonpartisanship have been deemed preferable to any Presidential or Congressional control over monetary policy.

The objectives and actions of the Federal Reserve could be markedly different from politicians, particularly in an election year. Politicians may focus on the short-term, favoring lower interest rates to boost economic growth and lower unemployment at the expense of longer-term inflation. The Federal Reserve’s mandate is to maximize employment with stable prices, which creates a challenging balancing act for determining the appropriate level of interest rates to accomplish both goals. While the goals may be realized in the long-run, there may be a dichotomy in the short-run. High inflation may require the Fed to increase interest rates to lower interest-rate sensitive consumer and business demand and consequently increase unemployment as economic growth declines. While low interest rates can spur economic growth and boost employment, the key is to not have economic growth expand too quickly, resulting in inflation and economic instability. In sum, it’s a balancing act for the Federal Reserve when setting interest rates, with a focus on serving the best interests of the United States through its dual mandate.

While the Federal Reserve currently operates with independence in regard to monetary policy, it does not have independence from fiscal policy (federal tax and government spending) decisions. Since 1980, the United States has had a budget surplus only once, in fiscal year 2001. Deficits are financed by the issuance of government debt, and the cumulative effect of budget deficits led to outstanding U.S. debt exceeding $37 trillion in 2025 with record interest expense of approximately $970 billion. The increasing debt and growing interest expense place additional stress on U.S. taxpayers, and the Federal Reserve. The U.S. government cannot default on debt, as the result would be severe, negative impacts on financial markets (including the money market) and dollar stability, and significantly undermine the United States’ global economic leadership. The choices for reducing debt and consequently interest expense are increasing government revenues through taxes, reducing government expenses through decreased funding of programs, or debt monetization.

Debt monetization (also known as quantitative easing) refers to the Federal Reserve issuing money to buy U.S. government debt. The increased monetary base will lower interest rates, reduce the amount of U.S. debt outstanding, and decrease interest expense. However, the potential side effect is an acceleration of inflation, as more money is chasing the existing supply of goods, with lower interest rates encouraging interest-rate sensitive consumers and businesses to increase spending.

The potential for debt monetization creates another possible dichotomy between what an independent Federal Reserve would do relative to Presidential or Congressional control. Since 1980, fiscal policy has driven budget deficits through government spending and tax reductions. Presidential or Congressional control over monetary policy could spur debt monetization to lower the level of debt and interest expense, yet tolerate increased inflation to lower the real value of outstanding debt. Inflation contributes to the K-shaped economy, as inflation will negatively impact lower-income households to a greater degree than upper-income households, as lower income households spend a greater percentage of their income on goods and services. Politicians could take credit for lowering the national debt at the expense of a growing K-shaped economy. The Federal Reserve focuses on its dual mandate of full-employment and stable prices, but implements debt monetization to reduce interest rates rather than political objectives.

There will almost always be disagreements as to what interest rate levels should be. However, the independence and dual mandate of the Federal Reserve is preferable to political mandates to maximize economic and financial market stability.

The Fed Funds Rate, Inflation and Unemployment

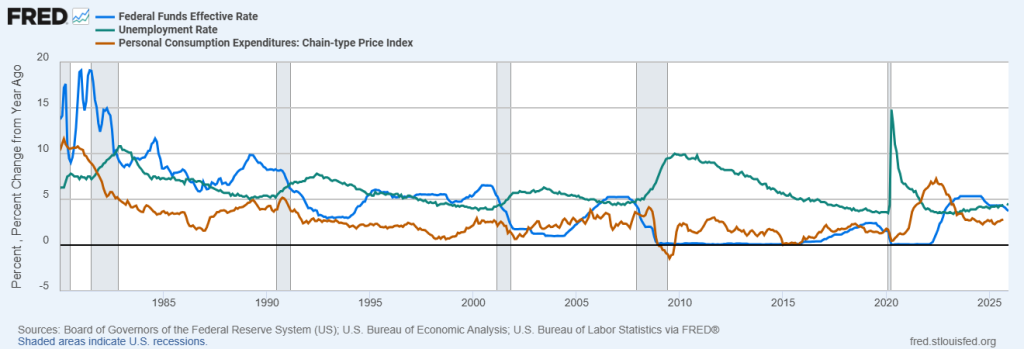

The Federal Reserve strives to achieve its dual mandate of maximum employment and price stability primarily through adjusting the fed funds rate. The Federal Reserve has generally lowered the fed funds rate to stimulate economic growth and increase employment in periods of economic recession or low economic growth. The Federal Reserve has generally increased the fed funds rate to lower interest rate sensitive consumer and business spending, particularly when employment is strong, during periods of relatively high inflation. The graph below shows the relationship since 1980 between the fed funds rate, unemployment rate, and the Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) inflation rate (as measured by the change in prices for personal consumption expenditures from one year ago). The fed funds rate is shown by the blue line, the unemployment rate is given by the green line, and the PCE inflation rate is shown by the orange line. Recession periods are shaded.

Fed Funds Rate, Unemployment Rate, PCE Inflation Rate: January 1980 – December 2025

- Blue Line – Federal Funds Effective Rate (percent)

- Orange Line – PCE Inflation Rate (percent change from year ago)

- Green Line – Unemployment Rate (percent)

Since 1980 the Federal Reserve has generally raised the fed funds rate when increasing PCE inflation has been above their 2% goal. The Federal Reserve can reduce pressure on prices by lowering consumer and business demand through increased interest rates when the economy is growing too quickly or bumping up next to full employment. However, battling inflation can be particularly challenging, as many factors contributing to inflation are outside of the Federal Reserve’s control. Those factors have included energy and commodity price spikes caused by war, supply chain problems, housing inventory shortages, food price increases caused by environmental factors, and most recently, tariffs. Periods of rising or high inflation resulting in fed funds rate increases included: 1980-1981, 1987-1989, 1999-2000, 2005-2006, 2017-2018, and 2021-2022.

Since 1980, there have been six periods of economic recession: 1) January 1980-July 1980, 2) July 1981-November 1982, 3) July 1990-March 1991, 4) March 2001-November 2001, 5) December 2007-June 2009, and 6) February 2020-April 2020. In each recessionary period, the Federal Reserve reduced the fed funds rate to spur interest rate sensitive consumer and business spending. In each case, the Federal Reserve policy contributed to pulling the U.S. out of recession and reducing unemployment. A variety of factors contributed to the economic recessions.

In the early 1980s, stagflation (high unemployment with high inflation) posed a significant problem for the Federal Reserve. In response to stubbornly high inflation exceeding 10%, the fed funds rate was dramatically increased and approached 20% by June 1981. The high interest rates led to a dramatic fall in inflation, but also dampened economic growth and caused the unemployment rate to soar over 10% by September 1981. In 1982, declining inflation and rising unemployment led to a reversal in fed policy and the fed funds rate declined to under 9% by December 1982. By the end of 1984 economic stability was returning, with the fed funds rate, inflation, and unemployment rate significantly decreasing.

By the end of the 1980s, economic growth contributed to inflation ramping up and approaching 5%. Interest rate increases resulting from high inflation combined with an oil price shock caused by the Gulf war pushed the U.S. economy into recession with rising unemployment in 1990. By early 1991 inflation declined resulting in a significant reduction in the fed funds rate which contributed to a return to economic growth.

In 2001, a brief recession occurred due to a variety of bumps to the economy. The dot.com bubble was over, and the technology heavy Nasdaq index declined over 75% between March 2000 and October 2002. The September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks contributed to the economic decline, and the financial markets were plagued by accounting scandals (Enron). The unemployment rate jumped from 3.9% in December 2000 to 5.7% by the end of 2001. The economic recession and jump in unemployment resulted in a lowering of the fed funds rate from 6.50% at the start of 2001 to 1.00% in 2003. Monetary policy, through interest rate cuts, contributed to a return to economic growth and declining unemployment.

By late 2007, a major shock to the U.S. economy was beginning in the housing market. Credit was easy and mortgage-backed securities allowed a transfer of risk from lenders to investors. Although a myriad of factors contributed to the financial crisis, easy credit, rising interest rates and lack of government oversight of the housing market lit the fuse for the economic implosion. Defaults occurred on mortgage loans and mortgage-backed securities, home prices plummeted, foreclosures increased significantly, and the economy and stock market began a decline in late 2007 that lasted until early 2009. The Federal Reserve slashed the fed funds rate three times in late 2007 and seven times in 2008 to spur consumer and business spending as the economy struggled. In December 2008, the fed funds rate was targeted at a record low of 0.00-0.25%. The rate cuts, combined with fiscal policy, led to the longest economic expansion in U.S. history between June 2009 and February 2020.

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic caused an economic shock that led to record unemployment of 14.8% in April 2020 and the loss of over 20 million jobs. The impact of COVID on the economy precipitated two interest rate cuts in early 2020 and the fed funds rate returned to its record low of 0.00-0.25% in March. Monetary policy, including interest rate cuts, and fiscal policy, contributed to a return of economic growth in the second half of 2020. The unemployment rate bottomed out at 3.4% in April 2023, the lowest level since 1969.

Summary

2026 will bring a change to the operating structure of the Federal Reserve. Exactly how much it changes remains to be seen. There will always be disagreements as to what the level of interest rates should be. However, the financial markets have generally viewed the nonpartisanship and ability of the Federal Reserve to operate independently, without interference from Congress or the President, as critically important to the long-term growth of the United States economy and financial market performance. In May, the term of the current Chairman of the Federal Reserve, Jerome Powell, is scheduled to end. The Chairman of the Federal Reserve serves a four-year term after being nominated by the President and confirmed by the Senate. Questions remain regarding the autonomy of the Federal Reserve with the next chair.

The Federal Reserve currently operates with independence regarding monetary policy, but not without accountability, as the Federal Reserve is required to report to Congress twice a year. The Federal Reserve was created by an act of Congress in 1913 and in 1977 was given the dual mandate of maximum employment and stable prices when implementing monetary policies. Changes to interest rates are determined by the Federal Open Market Committee voting process. Congress could alter the law, but the nonpartisanship, broad expertise of Federal Reserve members, and the democratic process of the Federal Open Market Committee have been deemed preferable to any Presidential or Congressional control over monetary policy. Federal Reserve policies have contributed to the U.S. economy being the largest in the world, approximately one and a half times the size of second place China. Since the turn of the century, Federal Reserve policies have contributed to the longest economic expansion in U.S. history and the strongest economic recovery since the pandemic.

For Further Information:

- From the Federal Reserve:

- Federal Reserve History

- The Board of Governors

- What is the Purpose of the Federal Reserve System?

- Monetary Policy: What are its Goals and How Does it Work?

- The Federal Open Market Committee

- Federal Reserve Economic Goals

- What is the Lowest Unemployment Rate that the Economy can Sustain?

- Why Does the Federal Reserve Aim for 2% Inflation in the Long-Run?

- Open Market Operations and the Fed Funds Rate

- From Greenbush Financial Group: How the Fed Votes to Lower Interest Rates (2025 Explained) | Greenbush Financial Group

- From the Brookings Institution: Why Is Federal Reserve Independent, and What Does It Mean in Practice?

Kevin Bahr is a professor emeritus of finance and chief analyst of the Center for Business and Economic Insight in the Sentry School of Business and Economics at the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point.