For many Americans, the labor market, inflation, and housing affordability are perhaps the most important economic measures that affect their daily lives and economic standard of living. This blog will focus on the labor market, which provides a mirror for the U.S. economy.

Economic growth continued in 2025, but not all was well with the American economy. Several measures indicated that the labor market was softening, and getting a job became more difficult, particularly for some demographics. In addition to labor market softness, inflation remains above the Federal Reserve’s 2% target and housing affordability remains difficult. Although consumer spending has driven economic growth, the top 10% of earners have become increasingly important in driving that growth. According to Moody’s Analytics, the top 10% of earners now account for nearly half of all U.S. consumer spending, a historic high. Those top earners accounted for 49% of consumer spending in the second quarter of 2025, up from approximately 46% in 2023 and 43% in 2020.

A variety of measures can be used to assess the labor market; this blog will cover many of them. Trends are more important than the data in any one month, as the labor market can be impacted by nonrecurring events, such as weather. In addition, data collection by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which provides much of the economic information for the labor market, was impacted by the October 2025 government shutdown.

The Unemployment Rate – Recent Trends

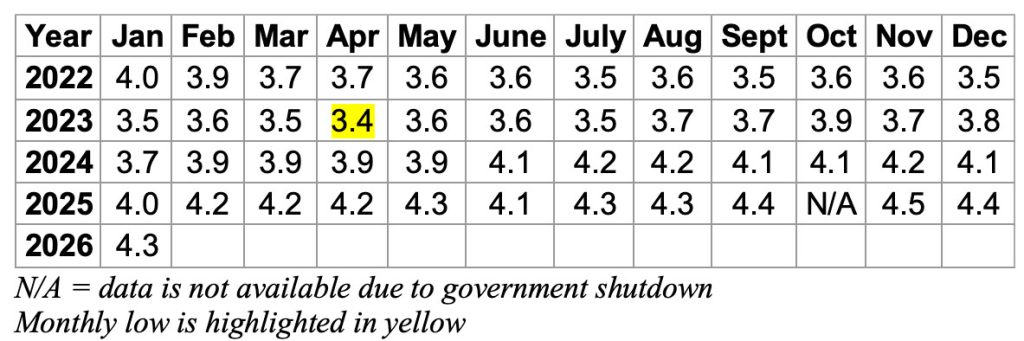

The table below shows the unemployment rate since 2022. The unemployment rate is the percentage of unemployed people in the labor force that are willing and available to work and who have actively sought work within the past four weeks.

Defining exactly what maximum employment is in terms of an absolute number is not easy. Recently, the benchmark for maximum employment without excessive inflation has been 3.5%. It became clear in the latter stages of the economic recovery in the last decade that an unemployment rate hovering around 3.5% could be sustained without leading to excessive inflation. In reality, it has been very difficult in recent history to move the unemployment rate below 3.5%, as there will always be a mismatch to some degree between the abilities of people looking for work and the skills required for available jobs. Since 1970, only one month had an unemployment rate below 3.5%, April 2023 at 3.4%.

Although the unemployment rate has been at relatively low levels since 2022, the rate generally trended up in 2025. The unemployment rate began the year at 4.0% and ended the year at 4.4%. After fluctuating between 4.0% and 4.5%, the rate appeared to be stabilizing at the end of 2025 and dropped to 4.3% in January 2026. However, the unemployment rate, and the number of unemployed people were both higher in January 2026 compared to January 2025. For January 2026, the number of unemployed people was at 7.4 million with an unemployment rate of 4.3%. This compares to 6.9 million unemployed in January 2025 with an unemployment rate of 4.0%.

Unemployment Rate January 2022–January 2026

Monthly Job Gains and Industry Employment – Recent Trends

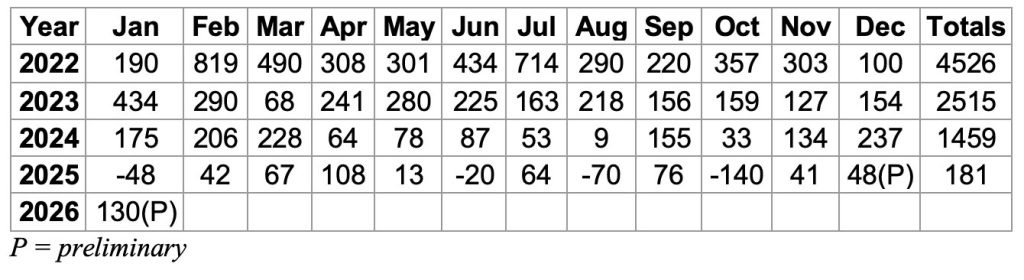

The table below shows total nonfarm monthly job gains since 2022. Following a robust 2022 with 4.5 million added jobs, 2023 cooled to a 2.5 million job increase. The softening continued in 2024 with 1.5 million added jobs. However, job gains occurred in each month between 2022 and 2024. The job market weakened considerably in 2025, with job losses occurring in the months of January, June, August, and October. Only 181,000 jobs were added for the entire year, an 87% drop from 2024. Preliminary job gains (subject to revision) for January 2026 were a solid 130,000 following the weak 2025, with job gains led by healthcare (82,000), social assistance (42,000) and construction (33,000). The January job gains may indicate a stabilizing, although continued challenging labor market. The January jobs number may have benefitted from fewer layoffs from seasonally sensitive industries like retailers, who hired less workers for the holidays than the prior year.

Monthly Job Gains

All Nonfarm Employees, thousands, Seasonally Adjusted

January 2022–January 2026

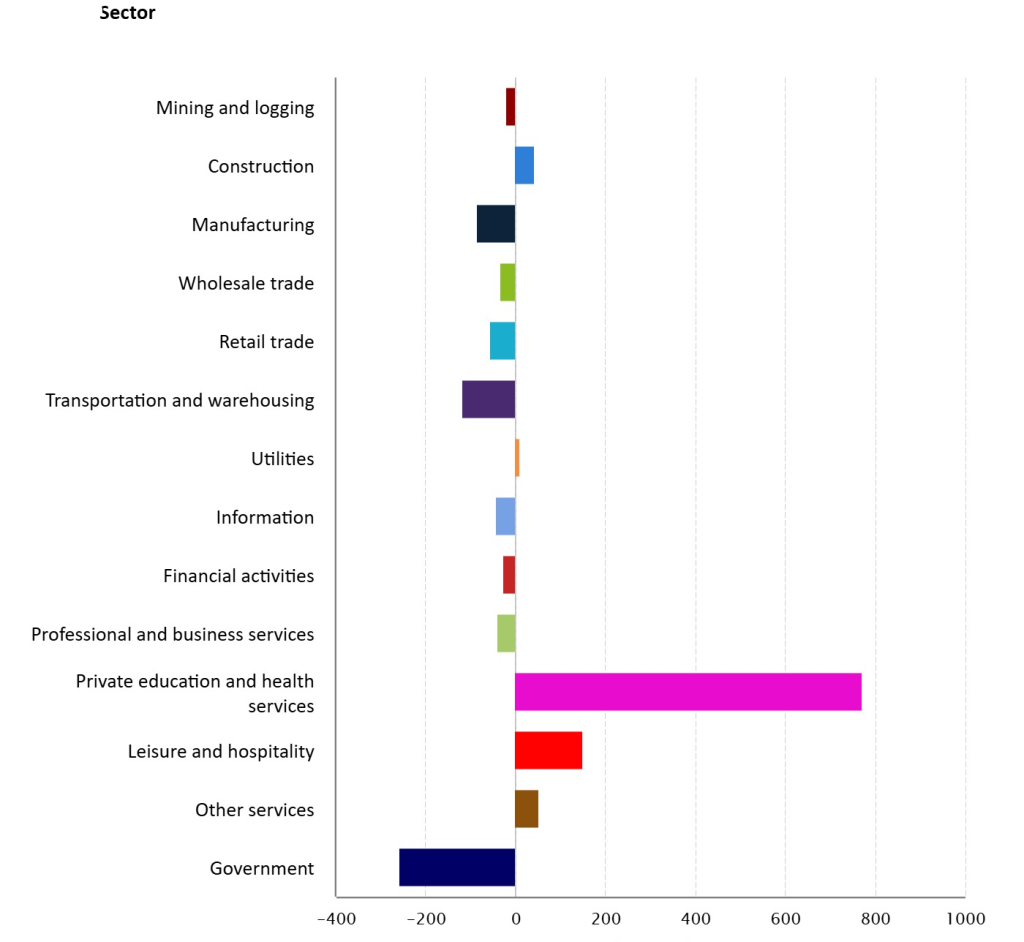

The chart below shows the change in employment for various industries for the 12 months ended January 2026. Private education and health services was the industry leader by far with an increase of 773,000 jobs. A distant second was leisure and hospitality with an increase of 150,000. Construction, other services, and utilities had modest job gains, but every other industry posted job losses over the past 12 months, reflecting an overall weakening labor market.

Employment Change by Industry, 12 Months Ended January 2026

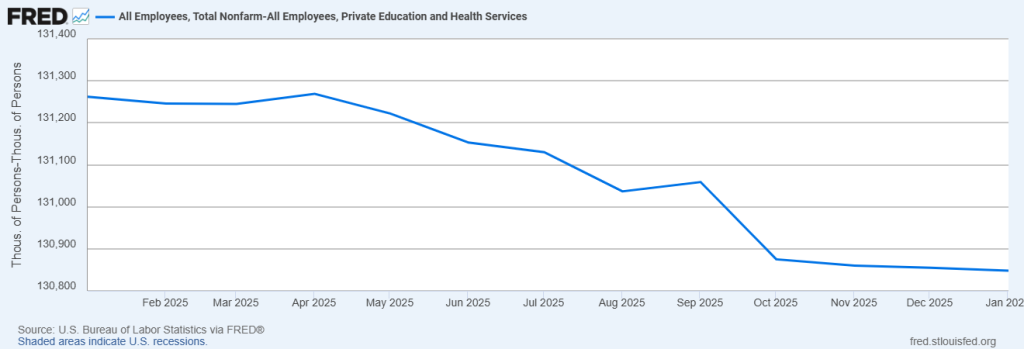

Private education and health services was the clear leader in adding jobs over the past 12 months. The graph below puts a perspective on the labor market when private education and health service jobs are excluded. The graph below shows monthly total nonfarm employment minus private education and health services employment over the past 12 months. When private education and health services employment is excluded, total nonfarm employment declined over the 12 months ended January 2026. In January 2026, total nonfarm employment excluding private education and health services was 130.848 million, compared to 131.262 million in January 2025, a decrease of 414,000. The graph provides further insight into a deteriorating labor market in 2025.

Total Nonfarm Employees Minus Private Education and Health Services Employees

January 2016 – January 2026

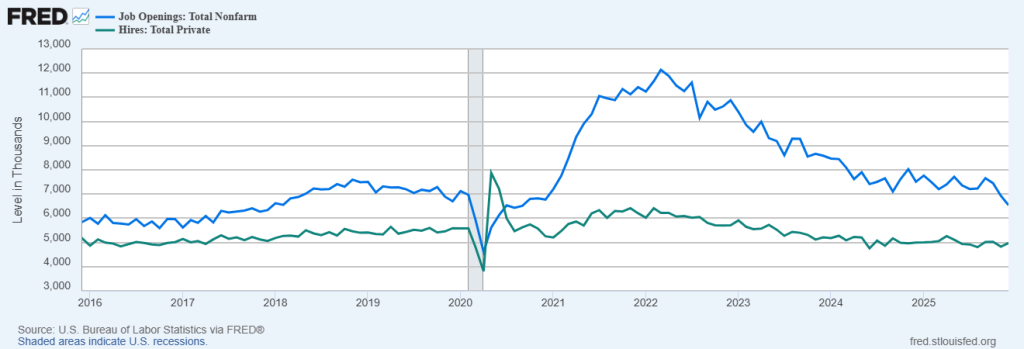

Job Openings and Private Sector Hires

The graph below shows job openings (blue line) and new private sector hires (green line) over a longer-term perspective, the 10-year period from January 2016 through December 2025. The shaded area indicates a period designated recession by the National Bureau of Economic Research. Recent trends in both job openings and new private sector hires generally reflected a softening labor market in 2025. After peaking in early 2022 following the recession, both the number of job openings and the number of private sector hires have fluctuated but generally trended downward. That trend continued in 2025.

2025 began with 7.8 million job openings, but the year ended with the fewest job openings since September 2020. The number of openings fell to 6.5 million in December, down from 6.9 million in November. In 2025, the number of private sector job hires peaked in April at 5.3 million before declining to 5.0 million in December.

Job Openings and New Private Sector Hires, thousands

January 2016 – December 2025

Layoffs and Permanent Job Losses

The number of layoffs to begin the year may reflect less 2026 economic optimism by employers. In January, according to outplacement firm Challenger, Gray & Christmas, employers cut 108,435 jobs, the biggest loss of jobs for the month of January since 2009. The layoffs were an increase of 118% from the January 2025 total of 49,795, and a 205% increase from the 35,533 job cuts announced in December. The January layoffs were the highest monthly total since October 2025 when 153,074 job cuts occurred.

The transportation industry led the job cuts with 31,243, primarily due to significant workforce cuts at UPS. Technology suffered 22,291 layoffs, with Amazon leading the way in layoffs. Major workforce reductions also occurred in Healthcare and Hospitals, with a loss of 17,107 jobs in January, the most since April 2020 for the industry.

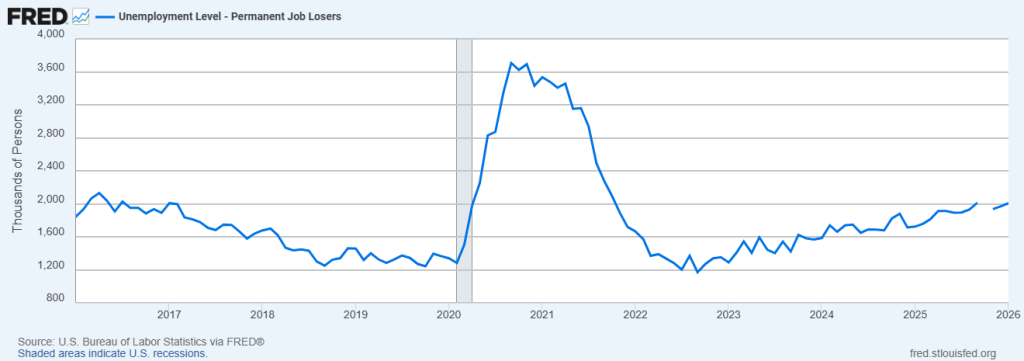

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics tracks permanent job losers, which is a more inclusive category than layoffs. Permanent job losers are classified as individuals who have left their jobs due to various reasons, including layoffs, restructurings, downsizing, and technology. The graph below shows permanent job losers since 2016. By either measure, layoffs or permanent job losers, the labor market weakened. Since September 2022, permanent job losers have fluctuated, but the trend is unmistakenly increasing. In 2025 that trend continued, with permanent job losers increasing from 1.72 million in January to 1.97 million in December, the highest level since October 2021.

The number increased to start the new year, rising to 2.01 million in January 2026. The growing number of layoffs and permanent job cuts in a period of economic growth increases labor market consternation, particularly with the growing presence of AI.

Permanent Job Losers

January 2016 – January 2026

(Data is not available for October 2025 due to the government shutdown.)

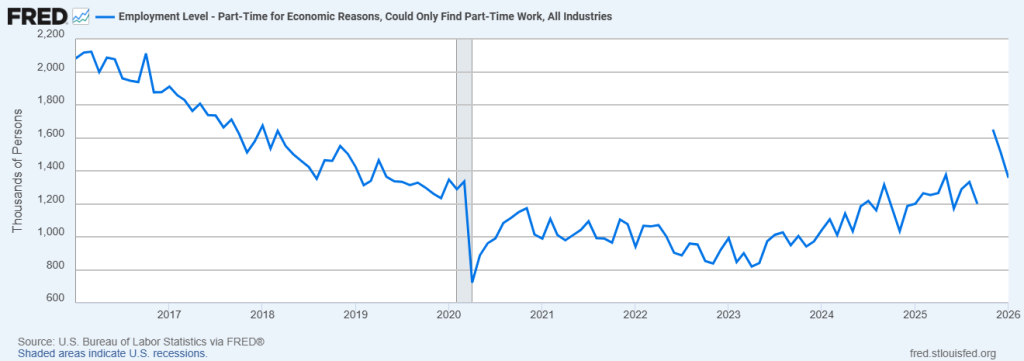

Part-time Employment

The graph below shows the number of workers employed part-time because they could only find part-time work. Since early 2023, the overall trend reflects a labor market softening. Although monthly fluctuations occurred, generally there was a long and steady decline from January 2016 through April 2023 in workers choosing part-time work because they could not find full-time work. The number of part-time workers that desired full-time work declined from 2.1 million in January 2016 to only 820,000 in April 2023. Since then, that number has trended up. 2025 began the year with 1.2 million part-time workers that desired full-time employment, with that number increasing nearly 25% to 1.5 million by December. The December 2025 total was the highest since November 2018. The number declined to 1.36 million in January 2026, perhaps another indication that the labor market may be stabilizing in a challenging environment.

Part-time Employees, Could Only Find Part-time Work, thousands

January 2016 – January 2026

(Data is not available for October 2025 due to the government shutdown.)

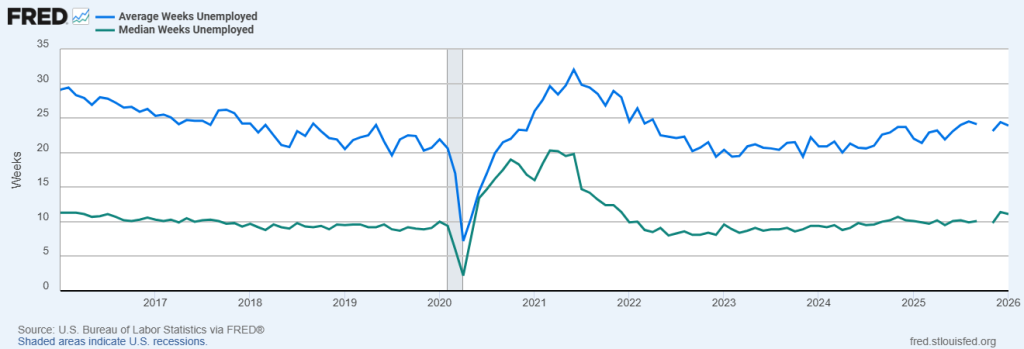

Length of Unemployment

Another sign of a softening labor market – an increasing length of unemployment for those looking for work. Slowly but surely, both the average and median weeks unemployed have generally been creeping up. The graph below shows the average length of unemployment (blue line) and the median length of unemployment (green line) over the past 10 years.

Continuing economic growth in the latter half of the last decade gradually decreased both the average and median length of unemployment. Following the economic recession of 2020, a spike occurred in the length of unemployment, with the average weeks unemployed peaking at 32 weeks in June 2021 and the median weeks unemployed hitting a high of 20.3 weeks in March 2021. After declining for approximately two years, the median and average weeks unemployed bottomed out at 8.1 and 19.4 weeks respectively, in December 2022. Both began increasing in 2023. That trend continued in 2025, with average weeks unemployed increasing from 22 weeks in January to 24.4 weeks in December. Median weeks unemployed rose from 10.1 to start the year to 11.4 to end the year.

2026 began with both the average and median weeks unemployed declining from December. In January 2026, the average weeks unemployed was 23.9 while the median weeks unemployed was 11.1. Although slight decreases from December, both measures increased from January 2025.

Average and Median Weeks Unemployed

January 2016 – January 2026

(Data is not available for October 2025 due to the government shutdown.)

Long-term Unemployed

Long-term unemployed is defined as individuals who have been unemployed for 27 weeks or longer and are actively seeking work. The graph below shows the number of long-term unemployed from January 2016 through January 2026.

After falling precipitously following the 2020 recession, the number of long-term unemployed bottomed out at 1.06 million in February 2023 before gradually rising. That trend continued through 2025, with the number of long-term unemployed rising from 1.45 million in January to 1.95 million in December, the highest number since December 2021. A slight decrease to 1.86 million occurred in January 2026.

Long-term Unemployed

January 2016 – January 2026

(Data is not available for October 2025 due to the government shutdown.)

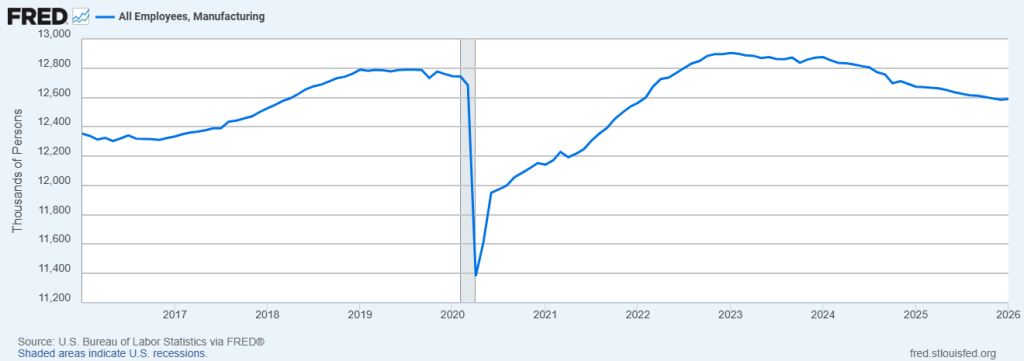

Manufacturing Employment

Part of the reason that the Trump Administration implemented global tariffs in 2025 was to bring back manufacturing jobs to America. Overall, in 2025, that didn’t happen.

The graph below shows manufacturing employment from January 2016 through January 2026. Manufacturing generally increased during the economic expansion of the last decade, peaking at 12.790 million in July 2019. Following the 2020 economic contraction, manufacturing employment recovered and reached a 10-year high of 12.903 million in January 2023. Since then, manufacturing employment had decreased, and that trend continued in 2025. In 2025, manufacturing employment decreased from 12.673 million in January 2025 to 12.585 million in December 2025, a decline of approximately 88,000 jobs.

January 2026 began the year with a very slight increase in manufacturing employment, with a gain of only approximately 5,000 jobs for a total of 12.590 million. The January 2026 total was still 83,000 fewer jobs than January 2025.

Manufacturing Employment, thousands

January 2016 – January 2026

Labor Force Participation

The labor force participation rate is defined by the U.S. government as the number of people in the labor force, either working or actively looking for work, as a percentage of the civilian noninstitutional population. The labor force participation rate can be impacted by secular trends not related to overall health of the economy. A significant factor has been the aging of the population, which increases retirements and reduces the labor force participation rate. The relatively strong stock market performance this decade has also contributed to retirements.

The graph below shows the labor force participation rate since 2016. Prior to the COVID driven recession, the labor force participation rate generally fluctuated between 62.5 and 63.5 percent, before drastically declining in 2020. Following COVID, the rate has generally been below pre-COVID levels, fluctuating around 62.5 percent and topping out at 62.8 percent in November, 2023. In 2025, the labor force participation rate started the year at 62.6 percent in January before ending the year at 62.4 percent in December. The rate was relatively unchanged at 62.5 in January 2026.

The Labor Force Participation Rate

January 2016 – January 2026

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Federal Reserve Economic Database

(Data is not available for October 2025 due to the government shutdown.)

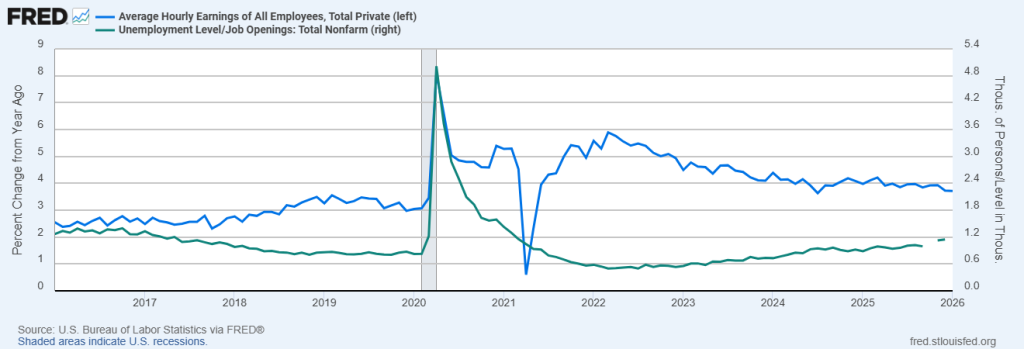

Wage Growth

The graph below shows the year-over-year average hourly wage growth of all private employees (blue line) relative to the number of unemployed persons per job opening (green line) from January 2016 through January 2026. The number of unemployed persons per job opening is a measure of the strength of the labor market, as it indicates how many job openings exist for each unemployed person. If the measure is below one, there are more jobs than unemployed people.

The graph below generally indicates a consistent relationship between wage growth and the number of unemployed persons per job opening. As the number of unemployed persons per job opening decreases, wages will generally increase as upward pressure is put on wages as employers compete for employees. As the number of unemployed persons per job opening increases, wage growth will generally decrease as employees become more readily available to employers.

Wage growth accelerated rapidly as the economy rebounded from the 2020 recession and employers competed for employees. Year-over-year wage growth peaked at 5.9% in March 2022 as the number of unemployed persons per job opening declined sharply from 2020 recession levels and approached 1.0. From May 2021 through September 2025, the number of unemployed persons per job opening was below 1.0. However, wage growth, although relatively strong, began decreasing in April 2022 as the number of unemployed persons per job opening generally increased. Wage growth remained over 5.0% until December 2022 and remained over 4.0% until June 2024.

In November 2025, the number of unemployed persons per job opening exceeded 1.0, the highest rate since April 2021. In December 2025, year-over-year wage growth was 3.7 percent while the number of unemployed persons per job opening was 1.15. The numbers reflected a stabilizing of the labor market (including wage growth), as the number of unemployed persons approximately matched the number of job openings.

January 2016 – January 2026

(Data is not available for October 2025 due to the government shutdown.)

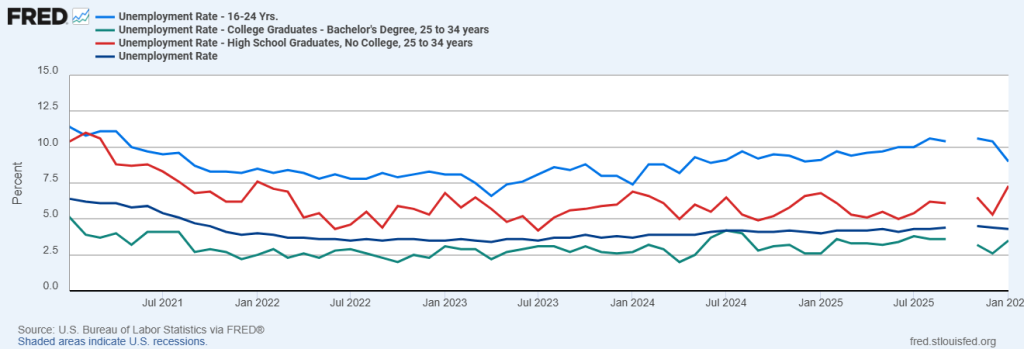

Labor Market Trends – Young Workers

The job market has been particularly challenging for young workers, including Gen Zers (born between 1997 and 2012). The graph below compares unemployment rates for four different worker groups: 1) Young workers aged 16-24 years (blue line), 2) College graduates, workers aged 25-34 years, (green line), 3) High school graduates, workers aged 25 to 34 years, (red line), and 4) All workers, (dark blue line). The graph shows unemployment rates for each group of workers following the 2020 recession.

The unemployment rate for young workers aged 16-24 years and high school graduates, workers aged 25-34 years, consistently exceeded the overall unemployment rate. The unemployment rate for college graduates, workers aged 25-34 years, was consistently less than the overall unemployment rate.

After declining following the 2020 recession and bottoming out at 6.6 percent in April 2023, the unemployment rate for young workers aged 16-24 years has generally trended upward and increased significantly. Between June and December 2025, the unemployment rate was at or exceeded 10.0%. The rate ended the year at 10.4%. For young workers aged 16-24 years, 2025 was the worst year for employment since 2021. The rate finally dipped below 10.0% in January 2026, with an unemployment rate of 9.0%. After hovering around 2.5% in 2022 and 2023, the unemployment rate for college graduates, workers aged 25-34 years, has generally increased slightly. The rate varied between 2.0% and 4.2% in 2024 and 2.6% and 3.8% in 2025 before closing the year at 2.6%. In January 2026, the rate increased to 3.5%. For high school graduates, workers aged 25 to 34 years, the unemployment rate fluctuated between 4.9% and 6.9% in 2024 and 2025 after bottoming out at 4.2% in July 2023. The rate ended 2025 at 5.3%, but jumped to 7.3% in January 2026, the highest unemployment rate since January 2022.

Unemployment Rate: Workers aged 16-24 years, College Graduates aged 25-34 years, High School Graduates aged 25-34 years, Overall

January 2021 – January 2026

(Data is not available for October 2025 due to the government shutdown.)

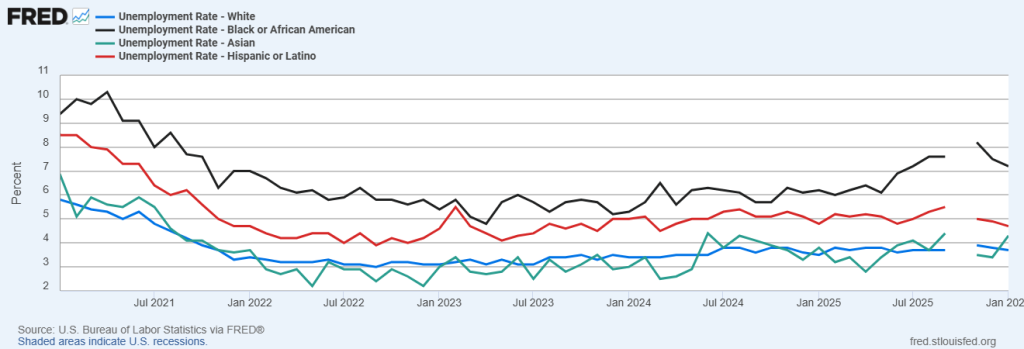

Unemployment Rates by Race

The graph below shows the unemployment rate since January 2021 for four different groups: 1) White (blue line), 2) Black or African American (black line), 3) Hispanic or Latino (red line), and 4) Asian (green line). Since January 2021, a consistent pattern of unemployment rates shows that, generally, the unemployment rate of Black or African Americans exceeds the unemployment rate of Hispanic or Latinos, the unemployment rate of Hispanic or Latinos exceeds the unemployment rate of Whites, and the unemployment rate of Whites generally tracks closely with the unemployment rate of Asians.

In 2025 the unemployment rate increased for three of the four groups. The unemployment rate for Blacks or African Americans increased from 6.2% in January to 7.5% in December, after hitting 8.2% in November. The November rate was the highest unemployment rate since 8.6% in August 2021. The January unemployment rate fell slightly to 7.2%. The December 2025 unemployment rate for Hispanic or Latinos was 4.9%, up very slightly from the January rate of 4.8%. The rate declined slightly in January 2026 to 4.7%. The unemployment rate for Whites rose from 3.5% in January 2025 to 3.8% in December before falling to 3.7% in January 2026. The unemployment rate for Asians fell from 3.8% in January to 3.4% in December before increasing to 4.3% in January 2026.

Unemployment Rate by Race

January 2021 – January 2026

Summary

By most measures, the labor market weakened in 2025. When private education and health services employment is excluded, total nonfarm employment declined over the 12 months ended January 2026. In January 2026, total nonfarm employment excluding private education and health services was 130.848 million, compared to 131.262 million in January 2025, a decrease of 414,000. An increase in the unemployment rate, declining job openings, an increase in permanent job losses, an increase in the number of workers accepting part-time positions because they couldn’t find full-time work, and an increase in the number of long-term unemployed all pointed to a weakened labor market in 2025 relative to 2024. Despite the global tariffs implemented by the United States in 2025, manufacturing employment declined. Young people had a particularly challenging labor market in 2025, with the unemployment rate for workers aged 16-24 years exceeding 10% at year’s end. For young workers, 2025 was the worst year for employment since 2021.

The labor market remained challenging but some stabilization appeared by the end of the year. In December 2025, the number of unemployed persons per job opening was 1.15, reflecting a more balanced labor market as the number of unemployed persons approximately matched the number of job openings. Wage growth moderated, the unemployment rate fell slightly and job gains returned, although the number of permanent job losers increased. The number of long-term unemployed and the average and median weeks unemployed all fell slightly as the new year kicked-off.

The labor market remains challenging with some signs of stabilization as the new year begins. Tariffs, economic uncertainty, and an increasing AI presence provide challenges to the 2026 labor market.

For More Information

- From the Dallas Federal Reserve: Consumption concentration may be up, adding slightly to economic fragility – Dallasfed.org

- From Moneywise: The top 10% of earners drive nearly half of all consumer spending. Is our economy too dependent on the wealthy?

- Info from the Bureau of Labor Statistics:

- Economic Situation

- Unemployment Rate

- Job Openings and Labor Turnover

- Labor Force Statistics

- All Employees, Nonfarm Payrolls

- CPS Tables : U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

- JOLTS Home: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

- Employment by industry, monthly changes

- Concepts and Definitions (CPS) : U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

- From the Associated Press: US job openings fall to 6.5 million, fewest since 2020, as labor market remains sluggish

- From Challenger, Gray, & Christmas: Challenger Report: January Job Cuts Surge; Lowest January Hiring on Record | Challenger, Gray & Christmas, Inc. | Outplacement & Career Transitioning Services

- From Moody’s Analytics: The Latest Analysis: Moody’s Analytics Economic View

Kevin Bahr is a professor emeritus of finance and chief analyst of the Center for Business and Economic Insight in the Sentry School of Business and Economics at the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point.