Recent political discussions have included the possibility of the U.S. defaulting on its debt. That would be irresponsible, costly, and foolish.

A quick review of why the discussion on the debt limit, commonly called the debt ceiling, is currently taking place. The debt limit is the maximum amount of debt that the Department of the Treasury can issue to the public or to other federal agencies. The amount is set by law and historically has been periodically increased to allow the financing of government operations. According to the Congressional Budget Office, the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019 (enacted in August 2019) suspended the limit through July 31, 2021. On August 1, 2021, the debt limit reset to the previous ceiling of $22.0 trillion, plus the cumulative borrowing that occurred during the period of suspension. Also, according to the Congressional Budget Office, if the debt limit remains unchanged, the ability to borrow would be exhausted and the Treasury expected to run out of cash in the first quarter of the next fiscal year (which begins on October 1, 2021).

According to the U.S. Treasury, “Congress has always acted when called upon to raise the debt limit. Since 1960, Congress has acted 78 separate times to permanently raise, temporarily extend, or revise the definition of the debt limit – 49 times under Republican presidents and 29 times under Democratic presidents. Congressional leaders in both parties have recognized that this is necessary.” There’s a reason for that. If you lend money to an individual, business, or government and they promise to pay you back, you expect to be paid back. If you are not paid back, there are consequences, including the likelihood that you will not lend money again to an entity that did not pay your original loan back. In addition, you might really need that loan repaid so you can meet your own expenses.

For the United States to be a global and economic leader, the U.S. should never default on its debt to investors. The “fiscal responsibility” of the United States should occur each year the U.S. budget is determined. Not paying back investors that lent money to the U.S. would be fiscal irresponsibility.

The federal budget deficit refers to U.S. federal government spending exceeding government income.

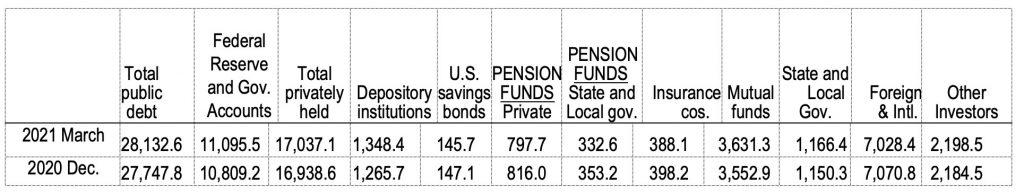

How does the United States government finance a budget deficit? It basically borrows money from the public through the issuance of U.S. government debt securities called U.S. Treasury securities. Who buys this stuff, who are the investors? Buyers include individuals (you could open an online account with the U.S. Treasury and purchase these securities), large institutional investors, certain mutual funds, pension funds, foreign investors, state and local governments, businesses, and certain U.S. government agencies. For a more complete breakdown, Table 1 below shows the detail of Treasury debt ownership provided by the U.S. Treasury. The table provides insight as to who could potentially be harmed if the U.S. defaults on its debt.

Table 1. Estimated Ownership of U.S. Treasury Securities

(billions of dollars)

The following is a list of who and what could potentially be harmed if the U.S. defaults on its debt:

- Any retiree receiving or expecting to receive payments from Social Security

- Workers having a pension fund that invests in Treasury securities, including private employees, federal employees, military, and state and local government employees

- Insurance companies and depository institutions that invest in Treasury securities

- Investors in money market mutual funds, or any fund that invests in Treasury securities

- State and local governments that invest in Treasury securities

- Foreign investors that purchased Treasury securities

- All U.S. taxpayers

- Consumers and businesses

- The U.S. economy

As of March 2021, a total of $28.1 trillion of U.S. debt was outstanding. Slightly over $11 trillion was held by the Federal Reserve and U.S. government agencies, with $17 trillion privately held. More specifically, according to the U.S. Treasury, approximately $6.125 trillion of Treasury securities were held by government agencies. Government agencies may invest in Treasury securities, generally viewed as a safe investment, if they have a temporary surplus of cash. The largest government agency investing in Treasury securities – Social Security.

Employers and employees each pay 6.2% (up to a salary limit of $142,800 in 2021) of an employee’s earnings for Social Security; 1.45% of earnings for Medicare. These current tax payments into Social Security are being dispersed to those receiving benefits now – excess payments remain in Social Security trust funds. There are separate trust funds for retirement and survivors benefits (the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) Trust Fund), disability benefits (the Disability Insurance (DI) Trust Fund), and Medicare. The Social Security Trust funds can purchase Treasury securities as an investment until funds are needed to pay benefits. Historically, current tax payments have exceeded disbursements, but that is changing. An August 2021 report released by Social Security indicated that the OASI Trust Fund is expected to be depleted by 2033, as annual disbursements are expected to exceed tax payments. Out of the $6.125 trillion total of Treasury securities held by government agencies in March 2021, the Social Security trust fund for retirement and survivors benefits (the OASI Trust Fund) owned nearly $2.8 trillion. If the U.S. government defaults on Treasury securities, the OASI Trust Fund could lose the funds invested in Treasury securities and could become depleted earlier. This could cause a reduction in benefits for retirees unless other sources of revenue are available. Other government funds that invest in Treasury securities that could lose money if defaults occur include the Military Retirement Fund, Medicare, Disability Insurance Trust Fund, and the Postal Service Retirement Fund.

Private pension funds and pension funds for state and local government employees combined for ownership of approximately $1.1 trillion of Treasury securities as of March 2021. Any default by the U.S. government could reduce the value of these pension assets, and consequently lower retirement benefits for pension plan participants.

Have you ever invested money in a money market mutual fund thinking it was a relatively safe investment? It was, but that could change if the U.S. government defaults on Treasury securities. Mutual funds, including money market mutual funds, invested over $3.6 trillion in Treasury securities as of March 2021. An investor in any fund that invests in Treasury securities could lose money.

Insurance companies and depository institutions combined for over $1.7 trillion of Treasury security holdings in March 2021. A default by the U.S. government could put a financial strain on the institutions holding Treasury securities. State and local governments owned nearly $1.2 trillion. Defaults on Treasury securities could result in a loss of funds desperately needed by state and local governments to meet expenses.

Outstanding U.S. Treasury debt owned by foreign investors was over $7.0 trillion in March 2021. Regarding the foreign investors, Japan and China are by far and away the major foreign investors in U.S. Treasury securities, each holding over $1 trillion of U.S. Treasury securities and combining for approximately 30% of the Treasury debt held by foreign investors. The United Kingdom is a distant third, holding only approximately 7% (approximately $500 billion) of the Treasury debt held by foreign investors. Any default would not be well received, and foreign investors have been a key source of financing for the United States, owning approximately 25% of outstanding Treasury debt. If foreign investors become wary of holding Treasury debt in the future, that source of financing would be difficult to replace. In addition, a decrease in the attractiveness of U.S. investments would weaken the U.S. dollar relative to foreign currencies, and the cost to the American consumer of imported goods would increase.

From a broader perspective, all U.S. taxpayers would be negatively impacted if the U.S. government defaults on Treasury securities. A default would cause interest rates to increase – if the U.S. needs to borrow more money in the future (and it will), that debt just became riskier for investors. There is a link between risk and return in the financial markets. More risk, more return is needed by investors. That would translate to higher interest rates on Treasury securities, and higher borrowing costs for the U.S. government and higher costs for taxpayers to repay. Would you lend money to the U.S. government knowing that you might not get repaid?

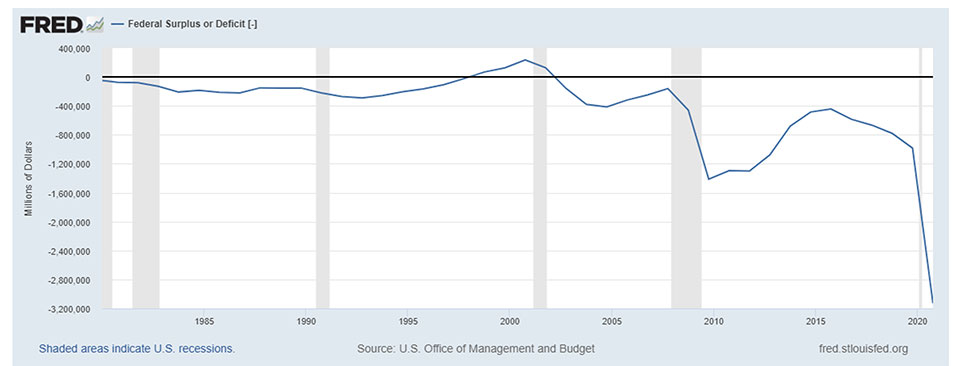

Regarding the U.S. need to borrow money, that need occurs when the U.S. government incurs a budget deficit. Except for a brief period between 1998 and 2001 when the U.S. was enjoying excellent economic growth and the tech boom in its internet infancy, the United States has had budget deficits since 1980. Now would not be the time to insist on the U.S. running a balanced budget while the economy is trying to recover from the pandemic in the midst of the delta variant surge. The budget deficit usually decreases during periods of economic growth. That, however, changed with the tax cuts of 2018, which contributed to increasing budget deficits during a period of economic growth that began in 2010 and ended with the onset of COVID-19.

Federal Budget Surplus or Deficit

Annual amount of Federal Budget Surplus or Deficit in Millions of Dollars (1980-2020)

A default on Treasury securities and failure to raise the debt ceiling would significantly derail a post-pandemic recovery and have traumatic effects on the U.S. economy. Moody’s Analytics estimates that a prolonged impasse and failure to raise the debt ceiling would cost the U.S. economy up to 6 million jobs, reduce household wealth by $15 trillion, and send the unemployment rate spiraling upward from approximately 5 percent to 9 percent.

Failure to raise the debt limit would have significant, negative effects on the financial markets. Higher required interest rates on future Treasury debt resulting from the increased risk would ripple through the economy and financial markets, increasing borrowing costs for business and consumers which would dampen and reverse any economic growth. Lower corporate profits and higher borrowing costs would make a bad combination for the stock market. Add to that the decline in consumer spending resulting from increased unemployment, and the stock market outlook would look bleak.

Finally, if the United States wishes to remain a global economic leader, stiffing foreign and domestic investors, hurting retirees (including private employees, federal, state, and local government employees, and military), negatively impacting international financial markets, and causing a global economic slowdown isn’t the way to do it. The U.S. would likely find it difficult to recover from the fall in reputation that would result in the international markets from any Treasury debt default.

In summary, there is much to be lost by many parties if the U.S. defaults on Treasury securities and the debt limit is not raised. Investors, retirees, U.S. taxpayers, businesses, consumers, financial markets, and the reputation of the U.S. as a global economic leader, would all take a hit. According to the United States Office of Government Ethics: “United States Treasury securities, often simply called Treasuries, are debt obligations issued by the United States Government and secured by the full faith and credit (the power to tax and borrow) of the United States.” If the U.S. defaults of Treasury securities, so much for believing the full faith and credit clause.

For further information:

- From the U.S. Treasury: U.S. Treasury – The Debt Limit

- From the Congressional Budget Office: Federal Debt and the Statutory Limit

- U.S. Budget Surplus or Deficit from the St. Louis Federal Reserve database

- Major Holders of U.S. Treasury Securities from the U.S. Treasury

- From the balance: Who Owns the National Debt?

- From the U.S. Treasury: Frequently Asked Questions About the Public Debt

- Data on Treasury Debt from the U.S. Treasury: Treasury Bulletin

- From Social Security: 2021 Trustee Report

- From Moody’s Analytics: Playing a Dangerous Game with the Debt Limit

- From the U.S. Office of Government Ethics: Treasury Securities

Kevin Bahr is a professor emeritus of finance and chief analyst of the Center for Business and Economic Insight in the Sentry School of Business and Economics at the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point.