Let’s continue with our Divisiveness and the Economic Challenges of 2021 series with Challenge #3 – Manufacturing and Trade.

The overall objectives for U.S. manufacturing and trade that most politicians could probably agree on would include strengthening U.S. manufacturing and expanding U.S. exports. Exactly how to do that becomes the divisive issue. In the past few years the U.S. has engaged in tariffs and trade wars with Canada, Mexico, the European Union, India, and most notably, China. U.S. companies offshoring the sourcing of inputs or products often faced a significant increase in costs, as they would be paying the tariffs. There was certainly a political divisiveness on the trade wars. A major problem with tariffs – there will be retaliatory tariffs. Harley-Davidson shifted production out of the U.S. due to European Union (EU) retaliatory tariffs on motorcycles after the U.S. imposed tariffs on imported aluminum and steel. The EU increased the tariffs on motorcycles from 6% to 31%; for Harley-Davidson to keep its products price competitive in the EU, sourcing from the U.S. was not a viable option.

Global supply chain networks have evolved for many companies and industries. Companies can source inputs and products globally in an attempt to minimize costs and expand markets. Ultimately, it is up to U.S. firms where to source inputs and products, and up to U.S. consumer what products to buy. Tariffs and trade wars can influence that decision, but ultimately U.S. imports are primarily a function of U.S. company sourcing decisions and U.S. customer buying decisions.

Not only did COVID-19 put a spotlight on U.S. reliance on foreign manufacturers for key medical supplies, but it also highlighted how supply chain interruptions can negatively impact healthcare and businesses. COVID-19 resulted in economic slowdowns and business lockdowns around the world. U.S. firms relying on a single foreign source were particularly vulnerable to supply chain disruptions from China. The pandemic demonstrated how relying on a single offshore source for inputs or products could negatively impact operations if the supply chain was disrupted.

The primary motivation for U.S. manufacturers to offshore is to lower costs. China in particular has provided cost and scale advantages. However, according to a July 2020 report by PwC, that may be changing. That doesn’t necessarily mean manufacturing jobs would be coming back to the U.S., it does mean that they would be leaving China. Other low cost countries, such as Indonesia, Mexico, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Thailand, have improved their supplier bases and manufacturing capabilities. The PwC study estimated that US manufacturers who choose to shift production from China could cut operating costs, on average, by an additional 23% if they near-shored to Mexico, and by 24% if they shifted to another Asian low cost country (LCC). Dual sourcing scenarios, which would include sourcing from China plus Mexico or another Asian LCC plus Mexico, could reduce sourcing costs for most companies by approximately 5-20% compared to sourcing and/or producing only in China. A survey of Chief Financial Officers (CFOs) by PwC indicated that nearly half (47%) of CFOs across industries agreed “developing additional, alternate sourcing options” was an important issue due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Any rebalancing of supply networks could take some time, due to logistics, workforce, and financing issues.

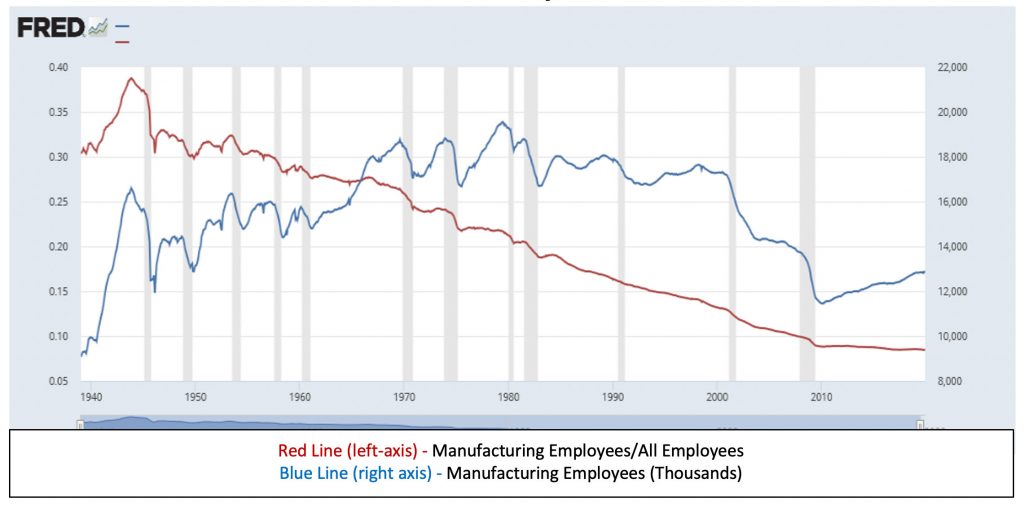

Offshoring has taken a toll on U.S. manufacturing. Manufacturing employment has generally been on a downward trend in the United States since 1980. Chart 1 below shows two lines. The blue line indicates the number of employees in manufacturing from 1939 through 2019. From 1939 through 1979 the number of people employed in the manufacturing sector generally increased, from a level of 9.3 million in 1939 to a peak of 19.5 million in 1979. A downward trend in manufacturing employment began in 1980. Although manufacturing employment rebounded slightly in the 1990s, the downward trend returned after the turn of the century with a sharp decline that generally continued through early 2010. After hitting a low of 11.5 million in early 2010, manufacturing employment generally grew each year throughout the entire decade, with only 2016 and 2019 having relatively unchanged manufacturing employment. Despite the growth in manufacturing employment during the economic expansion, the manufacturing sector ended the decade with almost 1 million fewer employees than what it had before the financial crisis. Manufacturing employment was 12.9 million in December 2019, an approximate 6.5% drop from the October 2007 level of 13.8 million.

The red line in Chart 1 below indicates the number of employees in manufacturing divided by total non-farm employment from 1939 through 2019 – the percentage of people employed in the manufacturing sector. As a percent of total employment, manufacturing employment peaked during World War II in October 1943 at 38.9%. However, after peaking in 1943, the percentage of people employed in the manufacturing sector has generally been on a long and steady decline. The recent decade began with manufacturing employment comprising 8.8% of total employment; the decade ended with manufacturing employment comprising only 8.5% of total employment. That compares to manufacturing employment comprising 13.8% of total employment in October 2007.

So, during the economic recovery employment in the manufacturing sector increased – just like employment in most sectors of the economy. Total manufacturing employment grew, but so did total employment in the economy. Manufacturing employment increased from 11.5 million to 12.9 million in the decade but was 6.5% lower than the 13.8 million manufacturing employment in October 2007 as the economic and financial crisis began. As a percentage of total employment, manufacturing employment decreased from a high of 12.0% in 2012 to 8.5% by the end of 2019. This compares to manufacturing employment comprising 13.8% of total employment in October 2007. Economic growth, significant corporate tax breaks from the 2018 tax bill, and tariffs and trade wars could not return manufacturing employment to the pre-financial crisis levels of 2007.

Chart 1: Manufacturing Employment and Manufacturing Employment as Percentage of Total Employment 1939-2019

Bringing manufacturing jobs back to the U.S. is challenging. Ultimately, firms could choose to onshore production for more than just cost reasons. However, the labor cost differential in manufacturing between the U.S. and China, Mexico, and Vietnam is substantial. According to the PwC study, average hourly compensation costs for manufacturing workers in the U.S. was approximately $40 per hour in 2019. This compares to China’s average hourly compensation costs for manufacturing workers of slightly over $5, and Mexico and Vietnam having lower labor costs than China. Shifting jobs back to the U.S. would result in higher labor costs, which could adversely impact product pricing, affecting both what U.S. consumers pay and a firm’s ability to compete against competitors.

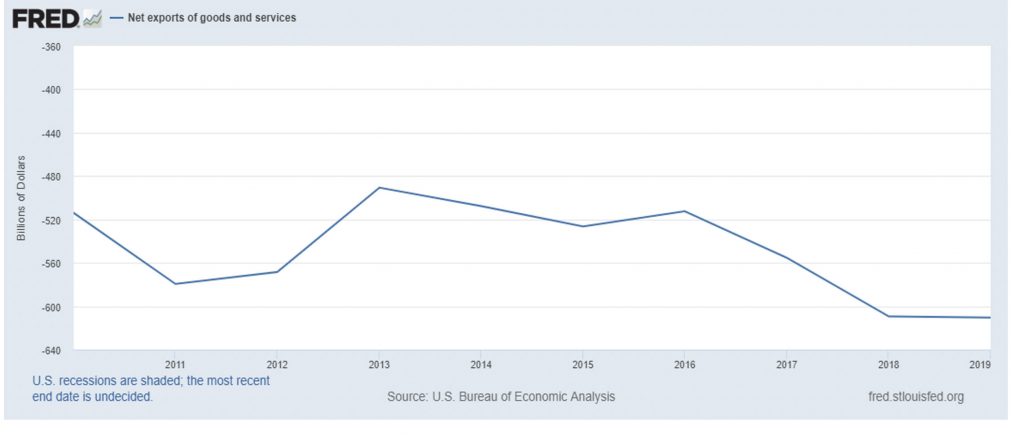

The tariff and trade wars did not have a positive impact on total U.S. net exports (exports minus imports) of goods and services. Chart 2 below shows U.S. net exports of goods and services over the last decade. Net exports of goods and services exceeded -$600 billion for 2018 and 2019, the highest levels of the decade, meaning that the U.S. imported approximately $600 billion more in goods and services from other countries than it exported to other countries.

Chart 2: U.S. Net Exports of Goods and Services 2010-2019

Bringing manufacturing jobs back to the U.S. is challenging. Tariffs and trade wars were generally ineffective in accomplishing that goal. Firms could onshore production for more reasons than cost, but the labor cost differential between foreign markets can be significant. If higher costs would result from producing in the U.S., there is the question of U.S. consumers willingness to pay higher prices for American goods. However, COVID-19 demonstrated that US. production of goods in certain industries (like healthcare) was vital to the country’s health. The challenge is to develop policies that promote U.S. production in key industries and make U.S. manufacturing a sourcing leader in essential products.

For further information:

- From PwC: Beyond China: US manufacturers are sizing up new−and more efficient global footprints

- From the Congressional Research Service (CRS): COVID-19: China Medical Supply Chains and Broader Trade Issues

- From the Peterson Institute for International Economics: Trump’s Trade War Timeline: An Up-to-Date Guide

- From the Federal Reserve Economic Database (FRED): U.S. Net Exports

- From the U.S. Census Bureau: Foreign Trade – U.S. Top Trading Partners

CBEI Series: Divisiveness and the Economic Challenges of 2021

Challenge #1: COVID-19 and the 2021 Economy

Challenge #2: Controlling U.S. Debt and Federal Budget Deficits

Challenge #3: Manufacturing and Trade

Challenge #4: Healthcare

Challenge #5: U.S. Economic Leadership

Challenge #6: Wages

Kevin Bahr is a professor emeritus of finance and chief analyst of the Center for Business and Economic Insight in the Sentry School of Business and Economics at the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point.